5.3. Letters and Interrogatories (1563-1586)

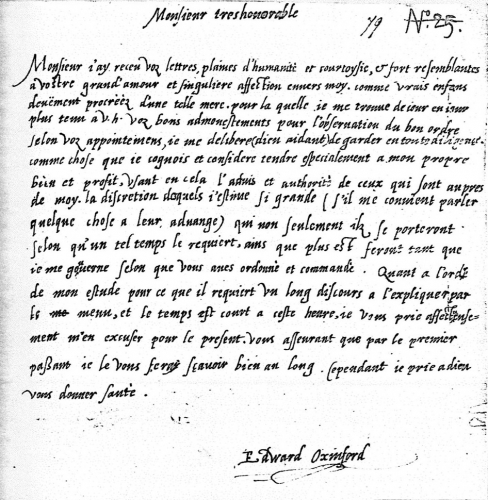

1. Oxford to Burghley, 19 August 1563

Monsieur treshonorable

Monsieur i’ay receu voz lettres, plaines d’humanite et courtoysie, & fort resemblantes a vostre grand’amour et singuliere affection envers moy. comme vrais enfans dueument procreez d’une telle mere. pour la quelle ie me trouve de iour en iour plus tenu a v. h. voz bons admonestements pour l’observation du bon ordre selon voz appointemens, ie me delibere (dieu aidant) de garder en toute diligence comme chose que ie cognois et considere tendre especialement a mon propre bien et profit, usant en cela l’advis et authorite de ceux qui sont aupres de moy. la discretion desquels i’estime si grande (s’il me convient parler quelque chose a leur advange) qui non seulement ilz se porteront selon qu’un tel temps le requiert, ains que plus est seront tant que ie me gouverne selon que vous avez ordonne et commande. Quant a l’ordre de mon estude pour ce que il requiert un long discours a l’expliquer par le menu, et le temps est court a ceste heure, ie vous prie affectueusement m’en excuser pour le present. vous asseurant que par le premier passant ie le vous ferai scavoir bien au long. Cependant ie prie a dieu vous donner sante.

Edward Oxinford

Source: BL Lansdowne 6[/25], f. 79

http://www.oxford-shakespeare.com/oxfordsletters1-44.html#03

With the publication of these letters on the internet Nina Green has provided a most helpful service. (See,http://www.oxford-shakespeare.com/index.html .) Unfortunately Green goes on to cast a false and very detrimental light on the entire oxfordian research. Without any apparent regard for historical facts or literary style she attributes diverse works from Robert Greene, Thomas Nashe, Martin Marprelate among others, to Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford.

1a. Translation by William P. Fowler[1]

My very honorable Sir

Sir, I have received your letters, full of humanity and courtesy, and strongly resembling your great love and singular affection towards me, like true children duly procreated of such a mother, for whom I find myself from day to day more bound to your honor. Your good admonishments for the observance of good order according to your appointed rules, I am resolved (God aiding) to keep with all diligence, as a thing that I may know and consider to tend especially to my own good and profit, using therein the advice and authority of those who are near me, whose discretion I esteem so great (if it is convenient to me to say something to their advantage) that not only will they comport themselves according as a given time requires it, but will as well do what is more, as long as I govern myself as you have ordered and commanded. As to the order of my study, because it requires a long discourse to explain it in detail, and the time is short at this hour, I pray you affectionately to excuse me therefrom for the present, assuring you that by the first passer-by I shall make it known to you at full length. In the meantime, I pray to God to give you health.

Edward Oxinford

2. Oxford to Burghley, 24 November 1569

Sir. Although my hap hath been so hard that it hath visited me of late with sickness, yet thanks be to God, through the looking to which I have had by your care had over me, I find my health restored and myself double beholding unto you, both for that and many good turns which I have received before of your part; for the which, although I have found you to not account of late of me as in time tofore, yet notwithstanding that strangeness[2], you shall see at last in me that I will acknowledge and not be ungrateful unto you for them, and not to deserve so ill a thought in you that they were ill bestowed in me, but at this present desiring you, if I have done anything amiss that I have merited your offence, impute to my young years and lack of experience to know my friends. And at this time I am bold to desire your favour and friendship, that you will suffer me to be employed by your means and help in this service that now is in hand, whereby I shall think myself the most bound unto you of any man in this court, and hereafter ye shall command me as any of your own. Having no other means whereby to speak with you myself, I am bold to impart my mind in paper, earnestly desiring your Lordship that, at this instant, as heretofore you have given me your good word to have me see the wars and services in strange and foreign places, sith you could not then obtain me licence of the Queen's Majesty, now you will do me so much honour as that, by your purchase of my licence[3], I may be called to the service of my prince and country, as at this present troublous time a number are. Thus leaving to importunate you with my earnest suit, I commit you to the hands of the Almighty.

By your assured friend this 24th of November.

Edward Oxenford

Source: BL Lansdowne 11[/53], ff. 121-2

Addressed: To the right honourable and his singular good friend Sir William Cecil, Secretary and Master of the Wards, give these. - Endorsed: Th’ Earl of Oxford to my master. Desires him to procure leave from the Queen for him to go & serve her & his country in the wars.

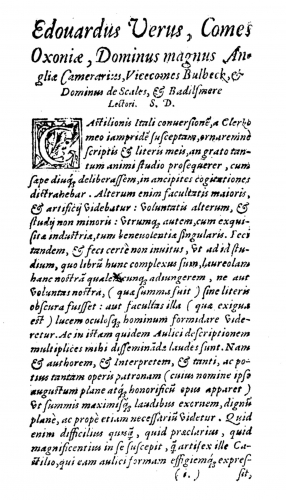

3. Dedication in Latin to Bartholomew Clerke's Translation of Castigloine’s Libro del Cortegiano, January 1572

Edouardus Verus, Comes Oxoniae, Dominus magnus Angliae Camerarius,

Vicecomes Bulbeck, & Dominus de Scales, & Badilsmere Lectori. S. D.

Castilionis Itali conuersionem, a Clerko meo iampridem susceptam, ornaremne scriptis & literis meis, an grato tantum animi studio prosequerer, cum saepe diuque deliberassem, in ancipites cogitationes distrahebar. Alterum enim facultatis maioris, & artificij videbatur : voluntatis alterum, & studij non minoris : vtrumque autem, cum exquisitae industriae, tum beneuolentiae singularis.

Feci tandem, & feci certe non inuitus, vt ad id studium, quo librum hunc complexus sum, laureolam hanc nostram qualemcunque adiungerem, ne aut voluntas nostra, (quae summa fuit) sine literis obscura fuisset : aut facultas illa (quae exigua est) lucem oculosque hominum formidare videretur.

Ac in istam quidem Aulici descriptionem multiplices mihi disseminandae laudes sunt.

Nam & authorem, & Interpretem, & tanti, ac potius tantam operis patronam (cuius nomine ipso augustum plane atque honorificum opus apparet) vt summis maximisque laudibus exornem, dignum plane, ac prope etiam necessarium videtur.

Quid enim difficilius quisquam, quid praeclarius, quid magnificentius in se suscepit, quam artifex ille Castilio, qui eam aulici formam effigiemque expressit, cui nihil addi possit, in quo nihil redundet, quem summum hominem & perfectissimum iudicemus ?

Itaque cum natura ipsa nihil omni ex parte perfectum expoliuerit : hominum autem mores, eam, quam tribuit natura, dignitatem peruertant [a printer’s error for praevertant?]: & seipsum vicit, qui reliquos vincit : & naturam superauit, quae a nemine vnquam superata est. Huc accedit, quam accurata res sit, quemadmodum in tanta Aulae magnificentia, tanto splendore hominum, tanto exterorum concursu, in ipsis etiam oculis vultuque principis viuendum sit, praecepta dare.

Quibus plura, atque maiora Castilio expressit. Quis enim de principibus viris maiori grauitate ? Quis de illustribus foeminis dignitate ampliori ? Nemo de re militari ornatius, de equorum concursionibus aptius, de conserendis in procinctis manibus praeclarius aut admirabilius. Non scribam, quanta cum concinnitate & praestantiae, in summis personis, virtutum ornamenta depinxerit : nec referam, in ijs, qui Aulici esse non possunt, quemadmodum aut vitium aliquod insigne, aut ridiculum ingenium, aut mores agrestes & inurbanos, aut speciem deformem delinearit. Quicquid est in sermonibus hominum, in congressu, & societate ciuili, aut decorum, atque ingenuum: aut deforme, & turpe : id eo habitu illustrauit, vt etiam oculis cerni posse videatur.

Huic tantarum rerum Autori, oratori etiam non indiserto, nouum lumen orationis accessit.

Latinus enim iam Aulicus, tanquam ex veteri illa vrbe Romana, in qua eloquentiae studia viguerunt, in curiam nostram vultum retulit, egregio habitu, summo apparatu, admiranda dignitate. Quod factum est Clerki nostri, cum incredibili ingenio, tum eloquentia singulari. Excitauit enim sopitam illam suam dicendi suauitatem : ornamenta & lumina, quae seposuit, ad res dignissimas reuocauit. Ergo maiori laude afficiendus cumulandusque est : qui rebus tantis (cum essent magnae) vt maiores essent maxima lumina & ornamenta adiecit.

Quis enim aut verborum vim plenius expressit ? aut sententiarum dignitatem illustrauit ornatius ? aut rerum varietatem artificiosius subsequitur ? Si res grauiores in sermonem incidant, verbis amplioribus & grauioribus explicat : si familiares & facetae, festiuis quidem atque argutis. Cum igitur & verbis pure atque ornate, & prudenter dilucideque sententijs, & toto elocutionis genere cum dignitate scribat : egregium quoddam ex hijs opus profluat atque promanet, necesse est. Mihi quidem tale videtur, vt Aulicum hunc Latinum cum lego, Crassum, Antonium, & Hortensium audire videar ijsdem de rebus disserentes.

Atque haec omnia tanta cum sint, fecit homo non imprudens, vt conuersionem suam vno omnium maximo ornamento illustraret. Quid enim potuit aut ad subsidium firmius, aut ad gloriam illustrius, aut ad fructum fieri vberius : quam quod Aulicum suum Illustrissimae amplissimaeque Principi dicauerit ? in quam cum omnes Aulicae virtutes transfusae sunt : tum diuiniores quaedam & plane caelestes infusae. Cuius praestantiam omnem si oratione complecti me posse existimarem, imprudens essem. Nulla est enim tanta scribendi vis, tantaque copiae, nullum tam apparatum orationis genus, quod illius virtus non superet.

Persapienter igitur interpres iste talem quaesiuit operis patronam, virtute quidem

praestantissimam, ingenio sapientissimam, Religione optimam, doctrina cum

excultissimam tum in alijs etiam literarum studiae exornantem [a printer’s error for studiis exornatam?].

Quae si sapientissimorum principum clarissima insignia, si florentis reipublicae

certissima praesidia, si optimorum ciuium ornamenta maxima & suo merito, & omnium iudicio, semper sunt habita : ea & autoritate tueri, & praemijs amplificare, & nominis sui titulo insignire : res profecto, cum omni Principe dignae, tum nostra videtur Principe dignissima, cui vni omnis omnium Musarum laus & literarum gloriae attribuendae videtur.

Ex Aula regia tertio Nonas Ianuarij. 1571 [=1572]

3a. Translation by Dr. Dana F. Sutton, Professor Emeritus of Classics, The University of California, Irvine.

Edward Vere, Earl of Oxford, Lord Great Chamberlain of England, Viscount Bulbeck, and Lord Scales and Baldesmere greets the reader.

I have been doubtfully dithering whether I should adorn this translation of Castiglione[4] the Italian, long since undertaken by my friend Clerke, with a written preface, or whether I should simply devote myself to it with a grateful mind, and I have often debated with myself at length and have been of varying opinions. For the one course seemed to require greater talent and art than I possess, whereas the other needed no less enthusiasm and care, and the both of them required particular industry and singular benevolence.

In the end I created this, and assuredly I did not do so unwillingly, so that I might add my own little laurel (of whatever quality it may be) to the relish with which I have embraced this book, lest either my enthusiasm (which has been great) might lie in obscurity without my written attestation, or my ability (which is small) might seem to fear the light and men’s eyes.

In my opinion, many forms of praise deserve to be accorded to this description of the courtier, and it appears worthy, indeed downright necessary, that I bestow the highest lauds on the author, the translator, and above all on the patroness of the work (thanks to whose very name it stands forth as a very august and honorable opus).

For what man has undertaken a more difficult, more distinguished, or grander task than the artistic Castiglione, who has limned a form and model of the courtier to which nothing can be added, in which nothing is superfluous, describing a man whom we should adjudge to be a consummate and perfect? Therefore, since nature herself has brought nothing to polished perfection in every respect, human manners should improve on that dignity conferred by nature, and Castiglione, who surpasses others, has both surpassed himself and bested nature (who has never been bested by any man). Then too, what a painstaking a business it is to set forth precepts on how to live in such great magnificence of a court, in such human splendor, among such a great concourse of foreigners, in the very eyes and presence of one’s sovereign!

Castiglione has done more and greater things than these. For who has written of princes with greater gravity, of famous women with more ample dignity? Nobody has written more lavishly of military matters, more to the point about cavalry encounters, more brilliantly or admirably about encounters on the field of battle. I shall not write about the great neatness and excellence with which he has depicted the ornaments of the virtues in personages of the highest rank. I shall not repeat how he has described the notable viciousness, silly character, uncouth and boorish manners, or unhandsome appearance that exist in those who are incapable of being courtiers. He has represented whatever exists in human conversation, intercourse and society that is either decorous and polite, or unsightly and debased, with such a quality that you seem to see it before your eyes.

The man who wrote about such important matters (even though he was no mean stylist) has been enhanced by this new light of eloquence. For now the Latin courtier has once more shown his face at our court (as if returned from that city of Rome wherein the pursuit of eloquence thrived), having an excellent appearance, equipped with consummate endowments, and wonderful dignity. This is the achievement of friend Clerke[5], accomplished with unbelievable genius and singular eloquence. For he has revived that dormant sweetness of speech he possesses; for these most worthy matters he has recalled the ornaments and lights he had set aside.

Therefore he is to be lauded and heaped with all the greater praise, that he has made such things, great as they are, yet more so by adding these lights and ornaments.

For who has expressed the significance of his words more fully? Or shone a more elegant light on the dignity of his sentences? If more serious matters come up in the discourse, he renders them in words more ample and grave, but if everyday and witty, he uses clever and witty ones. Since, therefore, he employs a pure and elegant vocabulary, writes his sentences with good style, prudence, and clarity, and employs an overall manner of eloquence marked by dignity, an excellent work must needs flow and derive from these things. It strikes me as such, with the result that, when I read this Latin Courtier, I seem to be hearing Crassus, Antony and Hortensius[6] conversing of these things.

And although all these things are such, this man has not imprudently ennobled his translation by a single greatest ornament. For how could he procure a stronger support, a brighter glory, or a richer fruit, than by dedicating his Courtier to our most illustrious and distinguished sovereign? Just as all the courtly virtues are imparted to her, so are more divine and heavenly ones. If I were to imagine I could encompass the whole of her excellence in my discourse, I should be a fool. Writing has no great power, no fertility of invention, no manner of discourse so splendid, that her virtue cannot surpass. Therefore this translator has in his wisdom sought a patroness for his work who is most outstanding in her virtue, most wise in her genius, the best in religion, and most well-furnished in erudition and well-equipped in other literary pursuits.

If the noblest distinctions of right wise sovereigns, thanks to their own deserts and according to the judgment of all men, are always to be reckoned the surest protection of their flourishing commonwealths, and the greatest adornment of their citizenries, then protecting one’s work by their authority and enhancing it by their rewards is a thing worthy of any sovereign, but most worthy of ours, to whom alone is to be credited all the praise of all the Muses and the glory of belles lettres.

Given at the royal court the third day of January 1571[7] [=1572]

Source: Balthasaris Castilionis comitis de curiali sive aulico libri quatuor ex Italico sermone in Latinum conversi. / Bartholomaeo Clerke Anglo Cantabrigiensi interprete. Londini : apud Iohannem Dayum typographum, an. Domini. 1571 [=1572]

http://www.oxford-shakespeare.com/ShortTitleCat/STC_4782_Courtier_1572.pdf

We may regard the publication of the Latin translation of Castiglione’s Libro del Cortegiano as being a testimonial from the aristocracy to Queen Elizabeth. The Queen was both the creator, and guarantor of the new urbanitas. (A code of behaviour for life in the city, modelled on ancient Rome). Along with Ariostos Orlando Furioso and Machiavellis Il Principe, Il Libro del Cortegiano, first printed in 1528, is one of the most significant works of Italian Renaissance literature.

Commenting Oxford's introduction to Clerk's translation, Gabriel Harvey said in 1578: “your Epistle testifies how much you excel in letters, being more courtly than Castiglione himself, more polished.” (Gratulationes Valdinenses of Gabriel Harvey, ed. by Thomas Hugh Jameson, 1938.)

4. To my loving friend Thomas Bedingfield Esquire (1572)

To my loving friend Thomas Bedingfield Esquire, one of Her Majesty's Gentlemen Pensioners.

After I had perused your letters, good Master Bedingfield[8], finding in them your request far differing from the desert of your labour, I could not choose but greatly doubt whether it were better for me to yield to your desire, or execute mine own intention towards the publishing of your book. For I do confess the affections that I have always borne towards you could move me not a little. But when I had thoroughly considered in my mind, of sundry and diverse arguments, whether it were best to obey mine affections, or the merits of your studies; at the length I determined it were better to deny your unlawful request than to grant or condescend to the concealment of so worthy a work. Whereby as you have been profited in the translating, so many may reap knowledge by the reading[9] of the same that shall comfort the afflicted, confirm the doubtful, encourage the coward, and lift up the base-minded man to achieve to any true sum or grade of virtue, whereto ought only the noble thoughts of men to be inclined.

And because next to the sacred letters of divinity, nothing doth persuade the same divinity, nothing more than philosophy, of which your book is plentifully stored, I thought myself to commit an unpardonable error to have murthered[10] the same in the waste bottom of my chests; and better I thought it were to displease one than to displease many; further considering so little a trifle cannot procure so great a breach of our amity, as may not with a little persuasion of reason be repaired again. And herein I am forced[11], like a good and politic captain, oftentimes to spoil and burn the corn of his own country, lest his enemies thereof do take advantage. For rather than so many of your countrymen should be deluded through my sinister means of your industry in studies (whereof you are bound in conscience to yield them an account) I am content to make spoil and havoc of your request, and that, that might have wrought greatly in me in this former respect, utterly to be of no effect or operation. And when you examine yourself, what doth avail a mass of gold to be continually imprisoned in your bags, and never to be employed to your use? Wherefore we have this Latin proverb: Scire tuum nihil est, nisi te scire hoc sciat alter[12]. What doth avail the tree unless it yield fruit unto another? What doth avail the vine unless another delighteth in the grape? What doth avail the rose unless another took pleasure in the smell? Why should this tree be accounted better than that tree but for the goodness of his fruit? Why should this rose be better esteemed than that rose[13] , unless in pleasantness of smell it far surpassed the other rose?

And so it is in all other things as well as in man. Why should this man be more esteemed than that man but for his virtue, through which every man desireth to be accounted of? Then you amongst men, I do not doubt, but will aspire to follow that virtuous path, to illuster yourself with the ornaments of virtue. And in mine opinion as it beautifieth a fair woman to be decked with pearls and precious stones, so much more it ornifieth a gentleman to be furnished with glittering virtues.

Wherefore, considering the small harm I do to you, the great good I do to others, I prefer mine own intention to discover your volume, before your request to secrete the same; wherein I may seem to you to play the part of the cunning and expert mediciner[14] or physician, who although his patient in the extremity of his burning fever is desirous of cold liquor or drink to qualify his sore thirst or rather kill his languishing body: yet for the danger he doth evidently know by his science to ensue, denieth him the same. So you being sick of so much doubt in your own proceedings, through which infirmity you are desirous to bury and insevill your works in the grave of oblivion: yet I, knowing the discommodities that shall redound to yourself thereby (and which is more unto your countrymen) as one that is willing to salve so great an inconvenience, am nothing dainty to deny your request.

Again we see, if our friends be dead we cannot show or declare our affection more than by erecting them of tombs, whereby when they be dead in deed, yet make we them live as it were again through their monument. But with me behold it happeneth far better; for in your lifetime I shall erect you such a monument that, as I say, in your lifetime you shall see how noble a shadow of your virtuous life shall hereafter remain when you are dead and gone[15]. And in your lifetime, again I say, I shall give you that monument and remembrance of your life whereby I may declare my good will, though with your ill will, as yet that I do bear you in your life.

Thus earnestly desiring you in this one request of mine (as I would yield to you in a great many) not to repugn the setting forth of your own proper studies, I bid you farewell.

From my new country Muses of Wivenghole[16], wishing you as you have begun, to proceed in these virtuous actions. For when all things shall else forsake us, virtue will ever abide with us, and when our bodies fall into the bowels of the earth, yet that shall mount with our minds into the highest heavens.

From your loving and assured friend, E. Oxenford.

Source: Cardanus Comforte translated into Englishe, And published by commaundement of the right honourable the Earle of Oxenford , [London]: Anno Domini 1573

Oxford's commendation poem: “The labouring man” and this letter together constitute the introduction toCardanus Comforte (Girolamo Cardano, De Consolatione, Venezia 1542). Bedingfield gives the date of his preface on “this first of January 1571 [=1572]”, even though the book was first published in 1573. Oxford's letter therefore dates from 1572.

Girolamo Cardano (1501-1576) was a mathematician, a physician, a philosopher and an astrologer whose achievements include the basis for mathematical probability theory and a modern autobiography. The following Shakespearian scholars have identified Cardanus Comforte as being “Hamlet's book” or the book that Hamlet is reading whilst pretending to be wandering aimlessly through the corridors of Helsingør Castle is a mentally deranged state: Francis Douce, Illustrations of Shakspeare and of Ancient Manners(1807), Joseph Hunter, New Illustrations of Shakespeare (1845), Lily B.Campbell, Shakespeare's Tragic Heroes (1930) and Hardin Craig, Hamlet's Book (Huntington Library Bulletin 6, 1934).

5. Oxford to Burghley, [London] September 1572

My Lord, I have understood by your Lordship's letters that Robert Christmas[17], according to my appointment, hath repaired to your good Lordship about my causes, and as your Lordship thinks good therein, as touching a new survey, so do I determine shall be done; for both as your Lordship perceives, and also myself, I have been greatly abused in the former by such as I put in trust tofore; but for that is past, now I have no other remedy but to look better to amend the fault in the rest of my dealings hereafter, and as for my timber at Colne Park, therein I had no other meaning save only to make, as it were, a yearly rent, so as I may without disparking the ground[18]. But now for the surveyor which your Lordship hath named, I must get him by your Lordship's means and for your Lordship's sake, for I am utterly unacquainted with him.

And as for those large leases which your Lordship hath been advertised of to be granted by me, I do assure your Lordship, without dissembling my faults to you to whom I perceive myself so much to be bound unto for your singular care over my well-doing, I must confess my negligence[19] and too little care, with the too much trust I have put to some over mine own doings; it may be I am greatly abused, but as yet, till I search into those things now, upon your Lordship's most gracious admonitions, I do not know, but it is likelier to be as your Lordship doth guess than otherwise and, if it be not so, it is more by good hap than of my providence.

The device of making free my copyholders, my Lord, I never thought of otherwise than a motion made to me by Robert Christmas wherein, among the other things, I bade him tell it your Lordship, at whose liking or disliking I was to be ruled in anything, knowing if it were a thing fit or unfit for me I should, by your Lordship's good advice, quickly understand, and so I left it to be not done, or taken in hand. And thus, sir, for these matters, both in this as in all other things, I am to be governed and commanded at your Lordship's good devotion.

I would to God your Lordship would let me understand some of your news (which here doth ring dolefully[20] in the ears of every man) of the murder of the Admiral of France and a number of noblemen and worthy gentlemen[21], and such as greatly have in their lifetimes honoured the Queen's Majesty our mistress, on whose tragedies we have a number of French Aeneases[22] in this city that tells of their own overthrows with tears falling from their eyes[23], a piteous thing to hear, but a cruel and far more grievous thing we must deem it then to see. All rumours here are but confused of those troops that are escaped from Paris and Rouen, where Monsieur hath also been and, like a vesper Sicilianus[24], as they say, that cruelty spreads over all France, whereof your Lordship is better advertised than we are here. And sith the world is so full of treasons and vile instruments daily to attempt new and unlooked for things, good my Lord, I shall affectiously and heartily desire your Lordship to be careful both of yourself and of her Majesty, that your friends may long enjoy you, and you them. I speak because I am not ignorant what practices have been made against your person lately by Madder[25] and later, as I understand, by foreign practices, if it be true. And think, if the Admiral in France was an eyesore or beam in the eyes of the papists, that the Lord Treasurer of England is a block and a cross-bar in their way[26], whose remove they will never stick to attempt, seeing they have prevailed so well in others'.

This estate hath depended on you a great while, as all the world doth judge; and now all men's eyes, not being occupied any more on these lost lords are, as it were, on a sudden bent and fixed on you, as a singular hope and pillar whereto the religion hath to lean. And blame me not, though I am bolder with your Lordship at this present than my custom is, for I am one that count myself a follower of yours now in all fortunes[27], and what shall hap to you, I count it hap to myself or, at the least, I will make myself a voluntary partaker of it.

Thus, my Lord, I humbly desire your Lordship to pardon my youth, but to take in good part my zeal and affection towards your Lordship, as on whom I have builded my foundation either to stand or fall. And good my Lord, think I do not this presumptuously, as to advise you that am but to take advice of your Lordship, but to admonish you as one with whom I would spend my blood and life, so much you have made me yours. And I do protest, there is nothing more desired of me than so to be taken and accounted of you. Thus, with my hearty commendations and your daughter's, we leave you to the custody of Almighty God. Your Lordship's affectioned son-in-law.

Edward Oxenford

Source: BL Harl. 6991[/5], ff. 9-10

Addressed: To the right honourable and his singular good Lord, the Lord Treasurer of England, give these.

6. Oxford to Burghley, London, 22 September 1572

My Lord, I received your letters when I rather looked to have seen yourself here[28] than to have heard from you, but sith it is so that your Lordship is otherwise affaired with the business of the Commonwealth than to be disposed to recreate yourself and repose ye among your own, yet we do hope after this, you having had so great a care of the Queen's Majesty's service, you will begin to have some respect of your own health, and take a pleasure to dwell where you have taken pain to build[29]. My wife (whom I thought should have taken her leave of you, if your Lordship had come, till you would have otherwise commanded) is departed unto the country[30] this day. Myself, as fast as I can get me out of town, do follow, until in her Majesty’s servive I be any way employed. I am content and desirous to try a foreign government for service whereby I may show myself dutiful to her. Otherwise, if it were not for that respect, I think there is more trouble than credit to be gotten in such governments. If there were any service to be done abroad, I had rather serve there than at home, where yet some honour were to be got; if there be any setting forth to sea, to which service I bear most affection, I shall desire your Lordship to give me and get me that favour and credit that I might make one. Which, if there be no such intention, then I shall be most willing to be employed on the sea-coasts, to be in a readiness[31] with my countryman against any invasion. Thus recommending myself to your good Lordship, I commit you to God. From London, this 22nd of September, by your Lordship's to command.

Edward Oxenford

Source: BL Lansdowne 14[/84], ff. 185-6

Addressed: To the right honourable his singular good Lord, the Lord Burghley, and Lord Treasurer of England, give these at the court.

Endorsed: The Earl of Oxford. Desires his Lordship to procure him some employment in the Queen’s service, but especially, which he chiefly bends to, at sea.

7. Oxford to Burghley, Wivenhoe, 31 October 1572

My Lord, your last letters, which be the first I have received of your Lordship's good opinion conceived towards me (which God grant so long to continue as I would be both desirous and diligent to seek the same), have not a little, after so many storms passed of your heavy grace towards me, lightened and disburdened my careful mind. And, sith I have been so little beholding to sinister reports[32], I hope now, with your Lordship's indifferent judgment, to be more plausible unto you than heretofore, through my careful deeds to please you which, hardly, either through my youth, or rather misfortune, hitherto I have done. But yet, lest those (I cannot tell how to term them but as backfriends[33] unto me) shall take place again to undo your Lordship's beginnings of well conceiving of me, I shall most earnestly desire your Lordship to forbear to believe too fast lest I, growing so slowly into your good opinion, may be undeservedly of my part rooted out of your favour, the which thing to always obtain, if your Lordship do but equally consider of me, may see by all the means possible in me I do aspire, though perhaps, by reason of my youth, your graver and severer years will not judge the same. Thus therefore, hoping the best in your Lordship and fearing the worst in myself[34], I take my leave lest my letters may become loathsome and tedious unto you to whom I wish to be most grateful. Written this 31st day of October by your loving son-in-law from Winehole[35].

Edward Oxenford

This bearer hath some need of your Lordship's favour which, when he shall speak with your Lordship, I pray you, for my sake he may find you the more his furtherer and helper in his cause.

Source: BL Lansdowne 14[/85], ff. 186-7

Addressed: To the right honourable my singular good Lord, the Lord Treasurer, give these at court. - Endorsed: 31 October 1572. Earl of Oxford. Upon a reconciliation of his father-in-law towards him.

A most elegant letter of reconciliation. Lord Burghley had carefully listed all of Oxford’s misdemeanors : “at Greenwich no bord wages for two grooms, usher, page, chamber keeper / after the cooks not paid / horses lent to Smith before the progress / new nags for £ 13 sent to Theobalds, unshod, no money to defray [disburse] / knocked up at 1 a clock, waked / kept out of his chamber at dinner and supper by [Rowland] York and others within / When [François] Montmorency came, no money to buy before he was landed / not speak a word nor countenance in father’s house / so many CLI [hundred and fiftys] spend of £ 10.000, come to his hand since marriage / a hose garter [order of the Garter] asked again / no pillion to come from Wivenhoe, but of poor fustian [cotton cloath]“ (Cecil Papers, XIV, pp. 19-20).

8. Oxford to Burghley, Paris, 17-18 March 1575

My Lord, your letters have made me a glad man, for these last have put me in assurance of that good fortune which your former mentioned doubtfully. I thank God therefore, with your Lordship, that it hath pleased Him to make me a father[36] where your Lordship is a grandfather and, if it be a boy, I shall likewise be the partaker with you in a greater contentation. But thereby to take an occasion to return, I am far off from that opinion, for now it hath pleased God to give me a son of my own (as I hope it is), methinks I have the better occasion to travel sith, whatsoever becometh of me, I leave behind me one to supply my duty and service either to my prince or else my country.

I thank your Lordship, I have received farther bills of credit and letters of great courtesy from Mr Benedict Spinola[37]. I am also beholding here unto Mr Reymondo[38], that hath helped me greatly with a number of favours, whom I shall desire your Lordship, when you have leisure and occasion, to give him thanks, for I know the greatest part of his friendship towards me[39] hath been in respect of your Lordship.

For fear of the Inquisition I dare not pass by Milan, the Bishop whereof exerciseth such tyranny[40]; wherefore I take the way of Germany where I mean to acquaint myself with Sturmius[41], with whom, after I have passed my journey which now I have in hand, I mean to pass some time.

I have found here this courtesy, the King[42] hath given me his letters of recommendation to his ambassador in the Turk's court; likewise, the Venetian ambassador[43] that is here, knowing my desire to see those parties, hath given me his letters to the Duke and divers of his kinsmen in Venice, to procure me their furtherances to my journey, which I am not yet assured to hold, for if the Turks come, as they be looked for, upon the coast of Italy or elsewhere, if I may, I will see the service; if he cometh not, then perhaps I will bestow two or three months to see Constantinople and some part of Greece[44].

The English ambassador here[45] greatly complaineth of the dearness of this country, and earnestly hath desired me to crave your Lordship's favour to consider the difference of his time from theirs which were before him. He saith the charges are greater, his ability less; the court removes long and oft; the causes of expense augmented, his allowance not being increased. But, as concerning these matters, now I have satisficed his desire, I refer them to your Lordship's discretion, that is better experienced than I perhaps informed him in negotiations of ambassadors.

My Lord, whereas I perceive by your Lordship's letters how hardly money is to be gotten, and that my man writeth that he would fain pay unto my creditors some part of that money which I have appointed to be made over unto me, good my Lord, let rather my creditors bear with me awhile and take their days assigned according to that order I left, than I to want in a strange country, unknowing yet what need I may have of money myself. My revenue I appointed with the profits of my lands to pay them as I may[46]and, if I cannot yet pay them as I would, yet as I can I will, but preferring mine own necessity before theirs[47]. And if at the end of my travel I shall have something left of my provision, they shall have it among them, but before, I will not disfurnish myself. Good my Lord, have an eye unto my men that I have put in trust. Thus making my commendations to your Lordship and my Lady, I commit you to God and, wheresoever I am, I rest at your Lordship's commandment. Written the 18th of March, from Paris.

Edward Oxenford

My Lord, this gentleman, Mr Corbeck, hath given me great cause to like of him, both for his courtesies that he hath shown me in letting me understand the difficulties as well as the safeties of my travel, as also I find him affected both to me and your Lordship. I pray your Lordship that those who are my friends may seem yours, as yours I esteem mine, and given your Lordship's good countenance, and, in short, I rest yours.

Source: Cecil Papers, 8/24

Addressed: To the right honourable and his singular good Lord, my Lord Treasurer of England, give these.

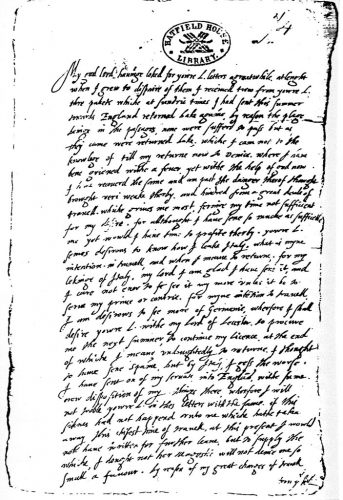

9. Oxford to Burghley, [Venice] 24 September [1575]

My good Lord, having looked for your Lordship's letters a great while, at length, when I grew to despair of them, I received two from your Lordship. Three packets which at sundry times I had sent this summer towards England returned back again by reason, the plague being in the passages, none were suffered to pass, but as they came were returned back[48], which I came not to the knowledge of till my return now to Venice[49], where I have been grieved with a fever. Yet, with the help of God, now I have recovered the same and am past the danger thereof, though brought very weak thereby and hindered from a great deal of travel, which grieves me most, fearing my time not sufficient for my desire, for although I have seen so much as sufficeth me, yet would I have time to profit thereby. Your Lordship seems desirous to know how I like Italy, what is mine intention in travel, and when I mean to return. For my liking of Italy, my Lord, I am glad I have seen it, and I care not ever to see it any more unless it be to serve my prince or country. For mine intention to travel, I am desirous to see more of Germany, wherefore I shall desire your Lordship, with my Lord of Leicester, to procure me the next summer to continue my licence, at the end of which I mean undoubtedly to return. I thought to have seen Spain, but by Italy I guess the worse. I have sent one of my servants into England with some new disposition of my things there, wherefore I will not trouble your Lordship in these letters with the same. If this sickness had not happened unto me, which hath taken away this chiefest time of travel, at this present I would not have written for further leave, but to supply the which I doubt not her Majesty will not deny me so small a favour.

By reason of my great charges of travel and sickness, I have taken up of Mr Baptisto Nigrone[50] 500 crowns, which I shall desire your Lordship to see there repaid, hoping by this time my money which is made of the sale of my land is all come in. Likewise I shall desire your Lordship that, whereas I had one Luke Atslowe[51] that served, who now is become a lewd subject to her Majesty and an evil member to his country, which had certain leases of me, I do think, according to law, he leeseth them all to the Queen sith he is become one of the Romish church, and there hath performed all such ceremonies as might reconcile himself to that church, having used lewd speeches against the Queen's Majesty's supremacy, legitimation, government and particular life, and is here, as it were, a practiser upon our nation. Then this is my desire, that your Lordship, if it be so as I do take it, would procure those leases into my hands again, whereas I have understood by my Lord of Bedford[52] they have hardly dealt with my tenants. Thus thanking your Lordship for your good news of my wife's delivery[53], I recommend myself unto your favour and, although I write for a few months more, yet, though I have them, so it may fall out I will shorten them myself. Written this 24th of September by your Lordship's to command.

Edward Oxenford

Source: Cecil Papers 160/74

Addressed: To the right honourable his singular good Lord, the Lord Treasurer of England.

10. Oxford to Burghley, Padua, 27 November [1575]

My Lord, having th'opportunity to write by this bearer who departeth from us here in Padua this night, although I cannot make so large a write as I would gladly desire, yet I thought it not fit to let so short a time slip, wherefore, remembering my commendations to your good Lordship, these shall be to desire you to pardon the shortness of my letters, and to impute it at this present to the haste of this messenger's departure. And, as concerning mine own matters, I shall desire your Lordship to make no stay of the sales of my land, but that all things (according to my determination before I came away, with those that I appointed last by my servant William Booth) might go forward according to mine order taken, without any other alteration. Thus recommending myself unto your Lordship again, and to my Lady your wife[54], with mine, I leave further to trouble your Lordship. From Padua, the 27th of November.

Your Lordship's to command. Edward Oxenford

Source: Cecil Papers 8/76

Addressed: To the right honourable and his very good Lord, my Lord Burghley, Lord Treasurer of England, give these. - Endorsed: The Earl of Oxenford to my lord from Padoua, the sale of his landes not to be stayed.

The messenger is waiting- three sentences, prologue, dictum and farewell. In this manner one can both make music out of language and strike hard and true.

Compare W. Shakespeare, Taming of the Shrew, I/1:

LUCENTIO. Tranio, since for the great desire I had

To see fair Padua, nursery of arts,

I am arriv'd for fruitful Lombardy,

The pleasant garden of great Italy,

And by my father's love and leave am arm'd

With his good will and thy good company,

My trusty servant well approv'd in all,

Here let us breathe, and haply institute

A course of learning and ingenious studies.

Pisa, renowned for grave citizens,

Gave me my being and my father first,

A merchant of great traffic through the world,

Vincentio, come of the Bentivolii;

Vincentio's son, brought up in Florence,

It shall become to serve all hopes conceiv'd,

To deck his fortune with his virtuous deeds.

And therefore, Tranio, for the time I study,

Virtue and that part of philosophy

Will I apply that treats of happiness

By virtue specially to be achiev'd.

11. Oxford to Burghley, Siena, 3 January [1576]

My Lord, I am sorry to hear how hard my fortune is in England, as I perceive by your Lordship's letters. But knowing how vain a thing it is to linger a necessary mischief, to know the worst of myself & to let your Lordship understand wherein I would use your honourable friendship, in short, I have thus determined that, whereas I understand the greatness of my debt and greediness of my creditors grows so dishonourable to me[55] and troublesome unto your Lordship that that land of mine which in Cornwall I have appointed to be sold (according to that first order for mine expenses in this travel) be gone through withal, and to stop my creditors' exclamations (or rather defamations I may call them), I shall desire your Lordship, by the virtue of this letter (which doth not err, as I take it, from any former purpose, which was that always upon my letter to authorize your Lordship to sell any portion of my land), that you will sell one hundred pound a year more of my land[56] where your Lordship shall think fittest, to disburden me of my debts to her Majesty[57], my sister, or elsewhere I am exclaimed upon. Likewise, most earnestly I shall desire your Lordship to look into the lands of my father's will which, my sister being paid[58] and the time expired, I take is to come into my hands. And if your Lordship will, for not troubling of yourself too much with my causes, command Lewen, Kelton and mine auditor to make a view into the same, I think it will be the sooner dispatched. As for Hulbert[59], I pray your Lordship to displace him of his office, which I restored unto him before mine auditor on condition he should render it up at all times that I should command. My reason is why I do the same, for that he bargained with me in Colne[60] and, trusting him, therein he hath taken more than I meant and, as his own letter which I have sent to my servant Kelton doth show, more than himself did mean (a fit excuse for so cozening a part). And yet though it was more than he meant, whereas it is conditioned that all times he should surrender the same when his money should be offered to him again in compass of certain years, yet, in mine absence, he hath refused the same, as I understand, whereupon methinketh he deserveth very evil at my hands. And he that in so small a matter doth misuse the trust I have reposed in him, I am to doubt his service in greater causes, wherefore I do again desire your Lordship to discharge him from all dealings of mine, upon his accounts to the rest of my forenamed servants.

In doing these things, your Lordship shall greatly pleasure me; in not doing them, you shall as much hinder me; for although to depart with land, your Lordship hath advised the contrary, and that your Lordship, for the good affection you bear unto me, could wish it otherwise, yet you see I have none other remedy[61]. I have no help but of mine own, and mine is made to serve me and myself not mine[62]. Whereupon till all such encumbrances be passed over, and till I can better settle myself at home, I have determined to continue my travel, the which thing in no wise I desire your Lordship to hinder[63], unless you would have it thus Ut nulla sit inter nos amicitia[64]. For having made an end of all hope to help myself by her Majesty's service, considering that my youth is objected unto me, and for every step of mine a block is found to be laid in my way, I see it is but vain calcitrarecontra li buoi[65] and, the worst of things being known, they are the more easier to be provided for, to bear and support them with patiency. Wherefore, for things passed amiss, to repent them it is too late, to help them (which I cannot, but ease them) that I am determined, to hope for anything I do not, but if anything do happen preter spem[66], I think before that time I must be so old as my sons, who shall enjoy them, must give the thanks, and I am to content myself according to this English proverb, that it is my hap to starve like the horse whilst the grass doth grow[67].

Thus, my good Lord, I do boldly write, that you should not be ignorant of anything that I do, for if I have reason, I make you the judge, and lay myself more open unto you than perhaps if I write fewer lines, or penned less store of words, otherwise I could do. But for that it is not so easy a matter at all times to convey letters from these parties into England, I am therefore the more desirous to use largely this opportunity, and to supply in writing the want of speaking, which the long distance between us hath taken away. Thus I leave your Lordship to the protection of Almighty God, whom I beseech to send you long and happy life, and better fortune to define your felicity in these your aged years than it hath pleased Him to grant in my youth, but of a hard beginning we may hope a good and easy ending[68]. Your Lordship's to command during life. The 3rd of January, from Siena.

Edward Oxenford

Source: Cecil Papers 8/12

Addressed: To the right honourable and his singular good Lord, my Lord Burghley, Lord Treasurer of England, give this.

12. Oxford to Burghley, 27 April [1576]

My Lord, although I have forborne, in some respect which I hold private to myself, either to write or come unto your Lordship, yet had I determined, as opportunity should have served me, to have accomplished the same in compass of a few days.

But now, urged thereunto by your letters to satisfy you the sooner, I must let your Lordship understand thus much.

That is, until I can better satisfy or advertise myself of some mislikes, I am not determined, as touching my wife, to accompany her. What they are, because some are not to be spoken of or written upon as imperfections[69], I will not deal withal. Some, that otherways discontent me, I will not blaze or publish until it please me. And, last of all, I mean not to weary my life any more with such troubles and molestations as I have endured; nor will I, to please your Lordship only, discontent myself. Wherefore, as your Lordship very well writeth unto me that you mean, if it standeth with my liking, to receive her into your house, these are likewise to let your Lordship understand that it doth very well content me; for there, as your daughter or her mother's, more than my wife, you may take comfort of her[70], and I, rid of the cumber thereby, shall remain well eased of many griefs. I do not doubt but she hath sufficient proportion for her being to live upon and to maintain herself[71]. This might have been done through private conference before, and had not needed to have been the fable of the world if you would have had the patience to have understood me, but I do not know by what or whose advice it was to run that course so contrary to my will or meaning, which made her disgraced to the world[72], raised suspicions openly, that with private conference might have been more silently handled[73], and hath given me more greater cause to mislike. Wherefore I desire your Lordship in these causes (now you shall understand me) not to urge me any farther; and so I write unto your Lordship, as you have done unto me, this Friday, the 27th of April.

Your Lordship's to be used in all things reasonable[74].

Edward Oxenford

Source: Cecil Papers 9/1

Addressed: To the right honourable and his very good lord, the Lord Burghley, Treasurer of England, give these.

On his return to England, Oxford is given to believe that his wife has been unfaithful to him. Lord Burghley notes retrospectively: “The Earl of Oxford arrived, being returned out of Italy, he was enticed by certain lewd Persons to be a Stranger to his Wife.”

All the evidence points to the fact that, Henry Howard, the brother of the executed Duke of Norfolk, wanted to set the seeds of antagonism between Oxford and Lord Burghley in order to win him over to the catholic cause. To this purpose he lied to his cousin about the behaviour of his wife, Anne Cecil, in his absence.

Oxford does not level any specific accusations, however the timbre and formulation of the letter leave no doubt as to the nature of the matters which he doesn't wish to discuss.

13. Oxford to Burghley, [13 July 1576]

My very good Lord. Yesterday, at your Lordship's earnest request, I had some conference with you about your daughter wherein, for that her Majesty had so often moved me, and for that you dealt so earnestly with me, to content as much as I could, I did agree that you might bring her to the court, with condition that she should not come when I was present nor at any time to have speech with me, and further that your Lordship should not urge farther in her cause. But now I understand that your Lordship means this day to bring her to the court, and that you mean afterward to prosecute the cause with further hope. Now if your Lordship shall do so, then shall you take more in hand than I have or can promise you. For always I have, and will still, prefer mine own content before others'[75] and, observing that wherein I may temper or moderate for your sake, I will do most willingly. Wherefore I shall desire your Lordship not to take advantage of my promise till you have given me some honourable assurance, by letter or word, of your performance of the condition which, being observed, I could yield, as it is my duty, to her Majesty's request, and bear with your fatherly desire towards her; otherwise, all that is done can stand to none effect. From my lodging at Charing Cross, this morning. Your Lordship's to employ.

Edward Oxenford

Source: Cecil Papers 9/15

Addressed: To the right honourable and his very good Lord, the Lord Treasurer of England, give these.

14. Oxford to the commissioners for the voyage to Meta Incognita[76], 21 May 1578

To my very loving friends William Pelham & Thomas Randolph, esquires, Mr Young, Mr Lok[77], Mr Hogan, Mr Field, & others the Commissioners for the voyage to Meta Incognita

After my very hearty commendations. Understanding of the wise proceeding & orderly dealing for the continuing of the voyage for the discovery of Cathay[78] by the north-west which this bearer, my friend Mr Frobisher[79], hath already very honourably attempted, and is now eftsoons to be employed for the better achieving thereof; And the rather induced, as well for the great liking her Majesty hath to have the same passage discovered, as also for the special good favour I bear to Mr Frobisher, to offer unto you to be an adventurer therein for the sum of one thousand pounds or more[80], if you like to admit thereof; Which sum or sums, upon your certificate of admittance, I will enter into bond[81] shall be paid for that use unto you upon Michaelmas day next coming; Requesting your answers therein, I bid you heartily farewell from the court the 21 of May, 1578.

Your loving friend, Edward Oxenford.

Source: The National Archives (Public Record Office), SP 12/149/42(15) f. 108v

http://www.oxford-shakespeare.com/StatePapers12/SP_12-149-42_f_108v.pdf

When we read these polite and gracious words, the first thing that springs to our attention is that Edward de Vere was a true gentleman. We find it hard to imagine what the “biographer” Alan H. Nelson could possibly have been thinking when he described the same man as being dishonest, cowardly and violent.

15. Answer of the Knight of the Tree of the Sun[82] (January 1581)

Callophisus[83] as it seems more covetous of glorie than able to merit, hath put his challenge to the print, but not his virtue to the proof. Yet to shadow his imperfection he hath covered himself under the wings of the most perfectest[84], for whom each would adventure: but against whom none will lift his lance. But whereas he vaunts himself to honor her above all, to love more, and serve more than any besides, this is so far beyond his compass, as the white knight is above him in zeal and worthiness, who albeit to me he be unknown, I praise his attempt wishing he had chosen a fitter day, wherein he might have had full means to have taught Callophisus his fault, and the worthiest wight have showed his desire to honor her whom he serveth in loyaltie. Wherefore as a friend to his mind and any other that in honor of that rare mistress which is accomplished with virtue's perfection and everie good quality which may enrich a mortal creature with immortal praise, being of none other to be spoken or understood but of her self, I mean to try my truth with no less valor than I have desire, not minding to disorder so noble a presence, but rather to entertain the same with a longer abode by diversity and change of arms, and to join with this worthieWhite Knight[85], if the next day may be given to the sword, as the former challenge is to the lance: not wandering from the rules of arms, neither wronging the rest of the defendants of which it is to be thought manie will make proof of their loyalties, as pleasure to their ladie. And as for Callophisus I know not whether the Red knight[86] having added a little to his challenge, hath not taken away a great part of his honor. But whereas either of them seem absolute preferers of themselves before all others in loyaltie, love, and worthiness, I must say and do avow, I am of a far contrarie opinion, and think either of them to be as unfit to usurp the title of her servants, as she worthie to be mistress of the world; as void of loyaltie, merit, valor and love, as she is complete with wisdom, grace, beautie and eloquence. Their works be as far less than their words, as their praise is short of her worth. And in this am I to assist the white knight unknown to me against the red knight in all points of arms that either the place will suffer, time permit, or Companie allow, and for the rest of his bragging words they may supply the want of his works. They nothing appertain to me who presume nothing, of myself, in respect of mine assurance in my mistress's virtue, and excellencie upon whose face their eyes are unworthie to look.

The Knight of the Tree of the Sun

Affronter to the Red.[87]

Source: British Library, Lansdowne 99, ff.259a-64b. In: Malone Society Collections, I.2. pp. 186-7.

http://www.oxford-shakespeare.com/BritishLibrary/BL_Lansdowne_99_ff_259a-64b.pdf

The classical, melodious style of this challenge matches the prose of William Shakespeare as we know it from: The introductions to Venus and Adonis (1593), The Rape of Lucrece (1594) and “The Argument” to Lucrece:

LUCIUS TARQUINIUS (for his excessive pride surnamed Superbus),after he had caused his own father-in-law, Servius Tullius, to be cruelly murdered, and, contrary to the Roman laws and customs, not requiring or staying for the people's suffrages, had possessed himself of the kingdom, went, accompanied with his sons and other noblemen of Rome, to besiege Ardea. During which siege the principal men of the army meeting one evening at the tent of Sextus Tarquinius, the king's son, in their discourses after supper, every one commended the virtues of his own wife; among whom Collatinus extolled the incomparable chastity of his wife Lucretia. In that pleasant humour they all posted to Rome; and intending, by their secret and sudden arrival, to make trial of that which every one had before avouched, only Collatinus finds his wife, though it were late in the night, spinning amongst her maids: the other ladies were all found dancing and revelling, or in several disports. Whereupon the noblemen yielded Collatinus the victory, and his wife the fame. At that time Sextus Tarquinius being inflamed with Lucrece's beauty, yet smothering his passions for the present, departed with the rest back to the camp; from whence he shortly after privily withdrew himself, and was (according to his estate) royally entertained and lodged by Lucrece at Collatium. The same night he treacherously stealeth into her chamber, violently ravished her, and early in the morning speedeth away. Lucrece, in this lamentable plight, hastily dispatched messengers, one to Rome for her father, another to the camp for Collatine. They came, the one accompanied with Junius Brutus, the other with Publius Valerius; and finding Lucrece attired in mourning habit, demanded the cause of her sorrow. She, first taking an oath of them for her revenge, revealed the actor, and whole manner of his dealing, and withal suddenly stabbed herself. Which done, with one consent they all vowed to root out the whole hated family of the Tarquins; and bearing the dead body to Rome, Brutus acquainted the people with the doer and manner of the vile deed, with a bitter invective against the tyranny of the king; wherewith the people were so moved, that with one consent and a general acclamation the Tarquins were all exiled, and the state government changed from kings to consuls.

16. Oxford’s First Interrogatory, 18 January 1581

Item, to be demanded of Charles Arundell[88] and Henry Howard[89]

What combination, for that is their term, was made at certain suppers, one in Fish Street, as I take it, another at my Lord of Northumberland's[90], for they have often spoken hereof and glanced in their speeches.

Further, for Henry Howard

If he never spake or heard these speeches spoken, that the King of Scots[91] began now to put on spurs on his heels, and so soon as the matter of Monsieur[92] were assured to be at an end, that then within six months we should see the Queen's Majesty to be the most troubled and discontented person living.

Further, the same

Hath said the Duke of Guise[93], who was a rare and gallant gentleman, should be the man to come into Scotland, who would breech her Majestie for all her wantonness, and it were good to let her take her humour for a while, for she had not long to play.

Item, to Charles Arundell

A little before Christmas at my lodging in Westminster, Swift being present, and George Gifford[94], [Arundell] talking of the order of living by money and difference between that and revenue by land, he said at the last if George Gifford could make three thousand pound he would set him into a course where he need not care for all England, and there he should live more to his content and with more reputation than ever he did or might hope for in England and they would make all the court here wonder to hear of them, with divers other brave and glorious speeches, whereat George Gifford replied, "God's blood, Charles, where is this?" He answered, if you have three thousand pound or can make it he could tell, the other saying, as he thought, he could find the means to make three thousand pound. That speech finished with the coming in of supper.

Item

Whether Charles Arundell did not steal over into Ireland within these five years without leave of her Majesty, and whether that year he was not reconciled or not to the church likewise, or how long after.

Item

When he was in Cornwall at Sir John Arundell's[95], what Jesuits or Jesuits he met there, and what company he carried with him of gentlemen.

Item

Not long before this said Christmas, entering into the speech of Monsieur, he passed into great terms against him, insomuch he said there was neither personage, religion, wit or constancy, and that for his part he had long since given over that course and taken another way, which was to Spain. For he never had opinion thereof since my Lord Chamberlain[96] played the cockscomb (so he termed my Lord at that time) as, when he had his enemy so low[97] as he might have trodden him quite underfoot, that then he would of his own obstinacy, following no man's advice but his own (which he said was his fault), bring all things to an

equality, wherein he was greatly abused, in his own conceit, and so discouraged Simier[98] as never after he had mind to Spain any longer, reputing the whole cause then to be overthrown. And, further, for Monsieur, a man now well enough known unto him, and he would be no more abused in him, and it was for nothing that Simier saved himself, for he knew his [Monsieur's] unconstancy, and Bussy d'Ambois[99] had been a sufficient warning unto him, whom Monsieur's treachery had caused to be slain and would by practise bring Simier into the slander thereof that his [Monsieur's] villainy might not be found, but it was plain enough. And he had made an end and quite done with the cause, and liked of it no more, and so with a great praising of the King of Spain's greatness, piety, wealth, and how God prospered him therefore in all his actions, not doubting but to see him monarch of all the world, and all should come to one faith, he made an end, and thus much considering his practise with Jerningham. And the other articles wherewith he is charged import a further knowledge, and gives some light to his dealings with these persons of religion and Irish causes wherein the King of Spain seems underhand to deal.

Source: Public Record Offive, SP12/151[/42], ff. 96-6v

http://www.oxford-shakespeare.com/StatePapers12/SP_12-151-42_f_96.pdf

A most dramatic incident occurred shortly before the Christmas of 1580. Oxford accused his two former friends Lord Henry Howard (1540-1614) and Charles Arundell (1539-1587) of a Catholic conspiracy against the crown. It turned out that the two men were traitors; they had deliberately stirred up ill feeling against Elizabeth whilst praising the glories of Spain.

On the strength of Oxford’s accusation Howard and Arundell were arrested and interrogated for months. In an attempt to discredit the Earl, the french ambassador Sieur de la Mauvissière (a friend of Mary Stuart) sent a report that was full of inconsistencies to King Henri III, in which he described Oxford as being a fallen catholic. Lord Howard responded to the charges of treason by saying that his accuser was an unbalanced malevolent wastrel. Arundell filled an accusation on 9 counts, and 70 sub-counts, including atheism perjury and murder. As I brought to attention in 2009, the historians Bossy (in 1959) and later Nelson (in 2003) along with their flock of sheep, took the accusations of the ingenious liar, Mauvissière along with the blatant libel of Howard and Arundell, copied it parrot style and made it the foundation of wild, ridiculous theories.

Queen Elizabeth was unmoved by the hysterical accusations of the two Catholics. Oxford was invited by the Queen to take part in the New Year’s festivities at court where she graciously accepted his gift: “A fair jewel of gold, being a beast of opals with a fair lozenged diamond, three great pearls pendant, fully garnished with small rubies, diamonds, and small pearls, one horn lacking”. Furthermore she expected his participation in a tournament that was to be held in honour of Philip Howard, Earl of Arundel and Surrey on 22 January 1581.

The interrogatories of 18 January who can execute a war of words with the speed and precision of an expert swordsman.

17. Oxford’s Second Interrogatory, 18 January 1581

Item, to my Lord Henry

How he came to the intelligence that there should come ambassadors of France, Spain and others which should assist the King of Scots' ambassador in the demand of his mother, and this should be determined among them on the other side, as he said, and shall shortly come to pass.

Likewise, both Charles and Henry

Likewise, they have been great searchers in her Majesty's wealth, having intelligence out of all her receipts from her Majesty's courts in law, customs (as well of them that go out as are brought in); what subsidies, privy seals, and fifteens she hath made since her coming to the crown; what helps, as they say, by the gatherings, as for the building of Paul's steeple, the lotteries, and other devises from the clergy; and what forfeits by attainder or otherwise, and what pensions, what other out of bishops' livings to some of her counsellors; what gifts she hath bestowed; what charges she was at in her household reparations of her houses and castles, fees and a number of things which now I cannot call to remembrance whereof they ordinarily would speak; and of her navy, the charge she was at; what the wars of Leith, Newhaven [Le Havre], and other petty journeys into Ireland and Scotland and in the time of the rebellion, which are too long; as well what she received as what she spended in all offices, places, etc.

Likewise, to the said Charles

For what cause he sent [his servant] Pike to La Mote[100], and who he was who went into Spain, and whether Pike went or no, but he assuredly remained the other's return who carried letters from La Mote and brought back again letters from the King [of Spain] and recompense, whereupon Pike returned with answer to Charles Arundell, who helped the man, as I heard, to a marriage. And whether the fellow brought his master [Arundell] some assurance and reward from the King, his master, I know not, but ever since he [Pike] lives of himself and gives no more attendance, to colour, as I conjecture, the cause better; and the course, as I guess and have great reason to conjecture, put into some other's hands, a thing which, if it be well looked into, cannot be void of great and some notable practise, if it will please her Majesty but to look into the zealous mind which the said Charles hath since carried more than covertly to the Mass.

Likewise, both Charles Arundell and Henry Howard are privy, as oftentimes they have declared by their speeches these last years past for 4 or 5,

What increase hath been made of souls to their church in every shire throughout the realm,

Who be of theirs and who be not, who be assured and who be inclined, for this difference they make between them that are reconciled and such as are affected to their opinion and are to be brought in, and in every shire throughout the realm where they be strong and where they be weak. And this is known by certain secret gatherings for the relief of them beyond the seas, wherein there be notes of very households.

Source: Public Record Office, SP15/28[/2], f. 3

http://www.oxford-shakespeare.com/StatePapersOther/SP_15-28-2_f_3.pdf

Endorsed: 18 January 158[1] Notes delivered by the Earl of Oxeford

18. Oxford to Burghley, [13] July 1581

My Lord, Robin Christmas[101] did yesterday tell me how honourably you had dealt with her Majesty as touching my liberty, and that as this day she had made promise to your Lordship that it should be. Unless your Lordship shall make some to put her Majesty in mind thereof, I fear, in these other causes of the two Lords[102], she will forget me, for she is nothing of her own disposition, as I find, so ready to deliver as speedy to commit[103], and every little trifle gives her matter for a long delay. I willed E. Hammond to report unto your Lordship her Majesty's message unto me by Mr Secretary Walsingham[104], which was to this effect: first, that she would have heard the matter again touching Henry Howard, Southwell[105] and Arundell; then, that she understood I meant to cut down all my woods, especially about my house, which she did not so well like of as if I should sell some land else otherwhere; and last, that she heard that I had been hardly used by some of my servants during this time of my commit, wherein she promised her aid, so far as she could with justice, to redress the loss I had sustained thereby, to which I made answer as I willed Hammond to relate unto your Lordship. Further, my Lord, whereof I am desirous something to write, I have understood of certain of my men have resorted unto your Lordship and sought, by false reports of other of their fellows, both to abuse your Lordship and me. But for that this bearer seems most herein to be touched, I have sent him unto your Lordship, as is his earnest desire, that your Lordship might so know him as your evil opinion, being conceived amiss by these lewd fellows, may be removed. And truly, my Lord, I hear of those things wherewith he is charged and, I can assure you, wrongfully and slanderously, but the world is so cunning as of a shadow they can make a substance, and of a likelihood a truth[106]. And these fellows, if they be those which I suppose, I do not doubt but so to decipher them to the world as easily your Lordship shall look into their lewdness and unfaithfulness, which, till my liberty, I mean to defer, as more mindful of that importing me most at this time than yet seeking to revenge myself of such perverse and impudent dealing of servants, which I know have not wanted encouragement and setting on. But letting these things pass for a while, I must not forget to give your Lordship those thanks which are due to you for this, your honourable dealing to her Majesty in my behalf, which I hope shall not be without effect, the which attending from the Court, I will take my leave of your Lordship, and rest at your commandment, at my house this morning.

Your Lordship's assured.

Edward Oxenford

Source: BL Lansdowne 33[/6], ff. 12-13

Addressed: For my Lord Treasurer. - Endorsed. July 1581 Earl of Oxford, thanks. Thanks his Lordship for obtaining a promise of his liberty of the Queen, entreating him to remember the Queen of him. The Queen’s message to him to Walsingham.

Either in the summer or the autumn of 1579 Edward de Vere fell in love with Anne Vavasour. She was eighteen or nineteen years old, she had black hair and she was beautiful. However, she was a lady-in-waiting to Queen Elizabeth. Anne became the mother of a son on 21 March 1581 and gave him the name of Edward. The Queen was absolutely livid, she regarded Oxford’s secret love affair as a blow to her own personal honour. She gave the order that both adulterers be thrown in the Tower without hesitation. – Oxford tried to flee the country but he was caught before he could board a ship. He and Vasavour remained in prison until 8 July 1581, after his release he was placed under house arrest.

19. Oxford to Burghley, [20 June] 1583

I have been an earnest suitor unto your Lordship for my Lord Lumley[107], that it would please you for my sake to stand his good Lord and friend which, as I perceive, your Lordship hath already very honourably [performed], for the which I am in a number of things more than I can reckon bound unto your Lordship, so am I in this likewise especially. For he hath matched with a near kinswoman[108] of mine to whose father I always was beholding unto[109] for his assured and kind disposition unto me. Further, among all the rest of my blood, this only remains in account either of me or else of them, as your Lordship doth know very well, the rest having embraced further alliances to leave their nearer consanguinity[110]. And as I hope your Lordship doth account me now one whom you have so much bound as I am to be yours before any else in the world, both through match, whereby I count my greatest stay, and by your Lordship's friendly usage and sticking by me in this time wherein I am hedged in with so many enemies[111], so likewise I hope your Lordship will take all them for your followers and most at command which are inclined and affected to me. Wherefore I shall once again be thus bold with your Lordship to be no more importunate[112] in this matter for your Lordship's favour in case my Lord Lumley's payment to her Majesty, wherein we do all give your Lordship thanks and you shall do me as great an honour herein as a profit if it had been to myself, in that through your Lordship's favour I shall be able to pleasure my friend and stand needless of others that have forsaken me. Thus, for that your Lordship is troubled with many matters where you are, I crave pardon for troubling you.

Your Lordship's to command.

Edward Oxenford

Source: BL Lansdowne 38[/62], ff. 158-9

Addressed: To the right honourable and his very good Lord, my Lord Treasurer of England, give these. - Endorsed: Earl of Oxford for the Lord Lumley 1583.

The Queen restored the Earl’s freedom on 14 July 1581 and as a token of reconciliation, she made him a present of a hat, fashioned in the Dutch style, of black taffeta, decorated with gold and pearls.

All the same, for the following two years he was a persona non grata at court and wasn’t invited to any royal functions.

20. Oxford to Burghley, 30 October 1584

It is not unknown to your Lordship that I have entered into a great number of bonds to such as have purchased lands of me, to discharge them of all encumbrances. And because I stand indebted unto her Majesty (as your Lordship knoweth), many of the said purchasers do greatly fear some trouble likely to fall upon them by reason of her Majesty's said debt, & especially if the lands of the Lord Darcy and Sir William Waldegrave should be extended for the same, who have two several statutes of great sums for their discharge. Whereupon many of the said purchasers have been suitors unto me to procure the discharging of her Majesty's said debt, and do seem very willing to bear the burden thereof if, by my means, the same might be stalled payable at some convenient days. I have therefore thought good to acquaint your Lordship with this their suit, requiring most earnestly your Lordship's furtherance in this behalf, whereby I shall be unburdened of a great care which I have for the saving of my honour and shall, by this means, also unburden my wife's jointure[113] of that charge which might happen hereafter to be imposed upon the same if God should call your Lordship and me away before her.

Your Lordship's

Edward Oxenford

My Lord, this other day your man Stainer told me that you sent for Amys, my man and, if he were absent, that Lyly should come unto you. I sent Amys, for he was in the way. And I think very strange that your Lordship should enter into that course toward me[114] whereby I must learn that I knew not before, both of your opinion and goodwill towards me. But I pray, my Lord, leave that course, for I mean not to be your ward nor your child. I serve her Majesty, and I am that I am[115], and by alliance near to your Lordship, but free, and scorn to be offered that injury to think I am so weak of government as to be ruled by servants, or not able to govern myself. If your Lordship take and follow this course, you deceive yourself and make me take another course than yet I have not thought of. Wherefore these shall be to desire your Lordship, if that I may make account of your friendship, that you will leave that course, as hurtful to us both.

Source: BL Lansdowne 42[/39], ff. 97-8

Addressed: To the right honourable my very good Lord, the Lord Treasurer of England. - Endorsed: 30 October 1584. The Earl of Oxford by Amice, his servant. For securing those that had purchased lands of him, he desires to take a course to pay his debt to the Queen.

Had any other person petitioned the Lord High Treasurer of England, we would be astonished to find such an open and uncompromisingly honest post script. In these casual, bold lines we recognise the literary style of the spear-shaker, the sudden change of the tone of the letter, the swing from light to dark, from quiet to loud, from bitter to sweet. The trap door through which the exposed traitors, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern disappear.