10.2. The Date of SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS

We assume that Shake-speare addressed the sonnets to a youth aged between 16 and 20 years – and from the text of the sonnets we can infer that the poet conceived them from the start as a cycle; we further know that the author was a prolific writer; we also remind sonnet 104, in which the poet states that their friendship had covered three winters and springs:

Such seems your beauty still: Three Winters’ cold,

Have from the forests shook three summers’ pride,

Three beauteous springs to yellow Autumn turned,

In process of the seasons have I seen,

Three April perfumes in three hot Junes burned,

Since first I saw you fresh which yet are green.

Can this timespan of probably three years be chronologically defined with precision?

The poet himself supplies a clue in sonnet 107:

Not mine own fears, nor the prophetic soul

Of the wide world, dreaming on things to come,

Can yet the lease of my true love control,

Supposed as forfeit to a confined doom.

The mortal Moon hath her eclipse endured,

And the sad Augurs mock their own presage,

Incertainties now crown themselves assured,

And peace proclaims Olives of endless age.

Now with the drops of this most balmy time

My love looks fresh, and death to me subscribes,

Since spite of him I'll live in this poor rhyme,

While he insults o’er dull and speechless tribes.

And thou in this shalt find thy monument,

When tyrants’ crests and tombs of brass are spent.

A new period of peace had set in, and the false prophets had been silenced. No prophecied doomsday can dissipate the hope for a better future, the poet writes. And though he does not lull into a false sense of security, nothing is said of a foreseeable end of his love: Not mine own fears …Can yet the lease of my true love control.

The mortal moon, which has suffered her eclipse has often been understood as an allusion to Queen Elizabeth who would have overcome the period of her political plight – in the year 1588 when England was thereatened by an invasion of the Spanish Army, the Armada. While Queen Elizabeth was, indeed, given the poetical surname Cynthia (also a surname of the goddess Diana representing the moon), the attribute “mortal” and its many negative connotations - mortal, lethal, murderous, fatal, deadly – seems inappropriate for so fortunate a queen. For this reason this interpretation seems quite inadequate.

To interpret the metaphor of the eclipsed moon as a reference to Elizabeth's death in the year 1603 seems therefore entirely out of character. Not only would the poet have committed an almost sacrilegious failure, he would, to boot, have referred to prophecies not yet made for the year 1603 – and associated his hopes for peace with a change of throne (which would have been contradictory after the death of the queen of peace.)

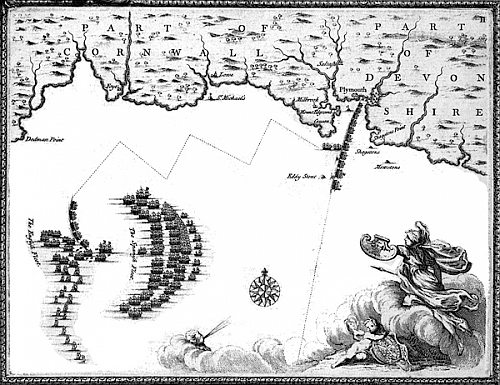

Already in 1899 Samuel Butler (Shakespeare’s Sonnets Reconsidered) asked: “Is there, apart from the ARMADA, between 1585 and 1609 any other event to which the image here conceived could be applied with equal force?“ It took almost half a century before Leslie Hotson (Shakespeare’s Sonnets Dated, 1949) convincingly solved the riddle of the „mortal moon“. He pointed out that in 1588 the Spanish Armada appeared off the English coast in a strategic crescent-shaped formation.

Shake-speare’s metaphor of the “mortal” or “lethal” is by now means the product of a poet’s fertile imagination. John Lea (1589) speaks of “a horned Moone of huge and mighty ships” [i] and in 1590 the Italian soldier and scholar in English service Petruccio Ubaldini (1524-1600) wrote: “Their fleet was placed in battle array after the manner of a moon crescent.” [ii] Phineas Fletcher (1627) describes the Spanish fleet as “a Moone of wood” – other contemporary are using similar circumlocutions.

The prophets and pessimists mock their own presages, Shakespeare writes. “A most balmy time” is dawning!

The most renowned prophecy of the time was that of the astronomer Johannes Regiomontanus (1436-1476) predicting the end of the world in the year 1588. It is not certain whether Regiomontanus is the true author of the following prophetic quatrain forecasting the end of the world and gripping Europe:

Thousand five hundred and eighty eight /

That’s the year I have in mind.

If in that year the world does not end /

A great wonder will none the less happen.

The prophecy was published for the first time in 1557 by Cyprian of

Leowitz. [iii]

A wonder occurred, though, in the year 1588, and it was a happy one for

England: the victory over the Armada. That is, Shake-speare’s sonnet 107 is

likely to have been written at a time when the the remembrance of the event was

still fresh enough to be remembered.

However, sonnet 107 may provide us with a point of reference for the chronology of the sonnets.

In 1598 the literary name dropper Francis Meres for the first time points to the sonnets, eleven years before their publication, in a both meticulous and tedious “Comparative discourse of our English Poets with the Greeke, Latine, and Italian Poets” as follows:

“As the soule of Euphorbus was thought to live in Pythagoras: so the sweete wittie soule of Ovid lives in mellifluous and honey-tongued Shakespeare, witnes his Venus and Adonis, his Lucrece, his sugred Sonnets among his private friends.”

The adjective sugared“ (like “sweet”) denotes the musicality and aesthetic perfection of the sonnets“ (the Greek poet Simonides, considered by Plato to be the foremost lyric poet, was surnamed Melikertes, meaning “honey cutter”; he was called “poeta Suavis”, the “sweet poet”, by Cicero in De natura deorum I.60)

Without Meres’s mention in the „Comparative discourse“ in Palladis Tamia (and the printing of the sonnets 138 and 144 in The Passionate Pilgrime, 1599) scholars would have located the composition of the sonnets in the 17th century, for nobody had ever mentioned them between 1599 and 1609.

But evidently Meres’s comparative discourse within the approximately 670 pages of the commonplace book Palladis Tamia were not written from one day to another, no more than the „sugared“ sonnets mentioned which, being circulated among Shakespeare’s private friends, might well have been so for a number of years before 1598, and Shakespeare could also have continued writing sonnets after 1598 (as are arguing those who advocates William Herbert, third Earl of Pembroke, as youth addressed in the sonnets). Given the paucity of definite time references in the SONNETS, which other way could be followed fo their reliable dating?

After having intensively studied the lyric poet SHAKE-SPEARE and looked at the string of contemporary English sonneteers (Constable, Daniel, Barnes, Drayton, Barnfield, E.C., Griffin etcetera), one cannot be but surprised at the little to no attention paid to the systematic scrutiny of the interdependency of these poets.

Who has imitated, quoted or, as it might also be termed, filched from whom at a given time?

To begin with, we should look at the aesthetic quality and skill of the authors in question– then at their age (for a fledgling poet often bows to one of riper age by imitating him) – then at their character, that is in how far each poet was stressing his originality or leant towards decent imitation – and, finally, perhaps his professionality. For not every writer between 1591 and 1599 exercising himself at the composition of sonnets saw in it a vocation; many were merely following a cultural fashion as a pastime.

As a general rule Shake-speare is viewed as having learnt or borrowed from the minor poets. He would have, so the tenet of the philologists for over half a century, been influenced, without intent of plagiarism, by the “minor poets” Daniel, Constable, Barnes, Drayton and Barnfield. In other words: the Incomparable would none the less have been a latecomer who would have copied from second- or third-rate poets (this conviction stems from the fact of Venus and Adonis being the first of Shakespeare’s works appearing in print in 1593 and the first mention of the Sonnets by Francis Meres in 1598, leading to the conclusion the poet cannot have started composing his sonnets earlier than 1593/4.)

But Shake-speare himself negates this view. In sonnet 78 he complains of his imitators,, “that every alien pen is now imitating him and busy exhorting the youth and addressing him own verses.

So oft have I invoked thee for my Muse,

And found such fair assistance in my verse,

As every Alien pen hath got my use,

And under thee their poesy disperse.

“Thine eyes,” he writes, “taught the dumb on high to sing,“ and spurred the self-conceited ignorance to a flight of fancy – and, perhaps alluding to the Earl of Essex – “added feathers to the learned’s wing to give grace a double majesty.” He calls the rival poet a thief, who grants the youth but what he has first him robbed of (79), characterises him as “a better spirit”, to make him (Shake-speare) tongue-tied (80), and goes on to accuse the rivals (now in the plural) of “gross painting” (82) whose rhethoric would at best be fit to give more gloss to bloodless cheeks.

And their gross painting might be better used,

Where cheeks need blood, in thee it is abused.

The youth would incur a curse if he were to pride himself of praise that disfigures him (84).

You to your beauteous blessings add a curse,

Being fond on praise, which makes your praises worse.

In sonnet 102 the poet pours his derision on the poetical starters and “starlings” chattering their love-songs from every bough (102).

But that wild music burthens every bough,

And sweets grown common lose their dear delight.

On the whole Shake-speare seems not to have been pleased with straying plagiators. And he himself would be one of them? And even be one of the most predatory? Brecht, one feels compelled to emphasize, would borrow from Villon – but not from Carossa. Shake-speare varies Ovid –- but not Constable!

So a systematic comparison is in order.

For only on condition to evidence when and since when Shake-speare’s contemporaries were imitating his SONNETS can provide us with sufficiently accurate dates.

But how could Shake-speare‘s rivals and followers have imitated his SONNETS if they had not yet been printed? – This objection, while certainly justified in modern times, cannot be applied to Elizabethan times. As Francis Meres clearly indicates, publication cannot be restricted to printing alone. None of Sir Philip Sidney’s works were printed during his lifetime. Sidney was particularly contemptuous about printing.

“And now that an over-faint quietness should seem to strew the house for poets, they are almost in as good reputation as the mountebanks at Venice. Truly even that, as of the one side it giveth great praise to poesy, which, like Venus — but to better purpose — hath rather be troubled in the net with Mars, than enjoy the homely quiet of Vulcan; so serves it for a piece of a reason why they are less-grateful to idle England, which now can scarce endure the pain of a pen. Upon this necessarily follows, that base men with servile wits undertake it, who think it enough if they can be rewarded of the printer. And so as Epaminondas is said, with the honor of his virtue to have made an office, by his exercising it, which before was contemptible, to become highly respected; so these men, no more but setting their names to it, by their own disgracefulness disgrace the most graceful poesy.” (An Apology for Poetry, written approximately 1579.)

But as H. R. Woudhuysen has demonstrated (Sir Philip Sidney and the Circulation of Manuscripts, 1559-1640, Oxford, 1996) Sidney himself was an eager distributor of his manuscripts. His friend Fulke Greville (later Lord Brooke), equally opposed to printing which in a well-known letter to Sir Francis Walsingham he condemned as “mercenary”, had not printed any of his works during his lifetime either.

“Witness his ... sugared sonnets among his private friends”, Francis Meres writes – „Among his private friends“ can only mean that this sonnets were not circulating in public, hence “unpublished”, or rather “unprinted”, but not unknown to a limited circle. Shake-speare's “private friends” knew his sonnets.

Typically, private poems and collections of lyric manuscripts were circulated in court circles, among members of the aristocracy and/or their clients.

An imperative of the behavioral codex of the Tudor era was the unwritten but widely accepted rule that an aristocratic author, be it a lyricist, dramatist or otherwise literary active writer, should not publish his own works in print during his lifetime. This behavioral rule making it indecorous or “ungentlemanlike” for an aristocratic author to publish his own lyrics, dramas or other merely literary works in print under his own name has been called “stigma of print”, which was essentially a stigma of verse, not a general stigma of print. The poetical works of courtiers like Henry Howard Earl of Surrey, Sir Thomas Wyatt, Thomas Lord Vaux, Sir Edward Dyer, Sir Walter Raleigh, Sir Philip Sidney, Ferdinando Stanley, Earl of Derby, and Sir Fulke Greville were only posthumously printed under their own name.

Another objection: in how far can the possible imitators of SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS be counted his “private friends” ?

As we cannot at this stage be certain about the identity of the poet, we may try to find out which persons had access or could have had access to the poetic manuscripts circulating in court circles.

Eleven english lyricical poets whose poems show a more or less pronounced affinity with the SONNETS between 1591 and 1599 are:

1. Henry Constable (ed. 1592, 1594)

2. Samuel Daniel (ed. 1591, 1592, 1594)

3. Barnabe Barnes (ed. 1593)

4. Giles Fletcher (ed. 1593)

5. Michael Drayton (ed. 1594, 1599)

6. Richard Barnfield (ed. 1594, 1595)

7. Edmund Spenser (ed. 1595)

8. Bartholomew Griffin (ed. 1596)

9. Gervase Markham (ed. 1597)

1. Henry Constable (1562-1613), son of Sir Robert Constable, member of Parliament, studied at St John’s College in Cambridge, was a friend of the young Earl of Essex, served at the court of Queen Elizabeth from 1588-1589, attended as representative of the Crown the wedding festivities of King James VI in Edinburgh in 1589, converted to the Catholic faith two years later and emigrated to France.

2. Samuel Daniel (1562-1619), son of a music-master, was admitted at Hertford College in Oxford, retainer of the Countess of Pembroke, sister of Sir Philip Sidney. Daniel was a friend of John Florio, Italian teacher of the third Earl of Southampton, and of Sir Fulke Greville, himself a poet and friend of Sir Philip Sidney. Daniel was known as a court poet.

3. Barnabe Barnes (1569-1609), son of Richard Barnes, bishop of Durham, entered Brasenose College, Oxford, in 1586, but left the university without taking a degree; in 1591 he took part in the campaign of the Earl of Essex before Rouen, France. He was acquainted with John Florio, who introduced him to the Earl of Southampton. He dedicated his first work Parthenophil and Parthenope to his “dearest friend” William Percy, himself a poet of little talent, third son of Henry Percy, 8th Earl of Northumberland and brother of Henry, 9th Earl of Northumberland, the “wizard Earl”.

4. Giles Fletcher (1546-1611), the Elder, son of Richard, Vicar of Bishop’s Storford, fellow of King’s College in Cambridge, where he became a lecturer. In 1584 he was elected a member of Parliament, in 1586 he was appointed as the Remembrancer of the City of London. (An official, representative of the City’s interests to Parliament and elsewhere).

5. Michael Drayton (1563-1631), born in the same county of Warwickshire as William Shaksper, was a page in the household of Thomas Goodyere of Collingham. He is reported to have studied in Oxford, dedicated his first work, a versification of biblical passage to Lady Jane Devereux, sister-in-law of the Earl of Essex with “gratitude for her generous hospitality.”

6. Richard Barnfield (1574-1626), son of he landowner Richard Barnfield , studied at Brasenose College in Oxford which he left for London without completing a degree and where he became acquainted with the poets Thomas Watson, Michael Drayton and Edmund Spenser. He also stood in close relation with William Stanley,6th Earl of Derby.

7. Edmund Spenser (1562-1599), along with Shake-speare the only peerless and “reigning” lyrical poet of the Elizabethan era, sohn of a tailor, visited the Merchant Taylor's School and studied at Pembroke College in Cambridge. Spenser, author of the famous epic poem The Faery Queene, was since 1579 a retainer of the powerful Earl of Leicester, through whom he became a friend of Sir Philip Sidney, author of the Arcadia.

8. Nothing more is known of Bartholomew Griffin than a cycle of 62 sonnets, published in 1596 and prefeced with a dedication to William Essex of Lamborn and an epistle to the “Gentlemen of the Inns of Court”.

9. Gervase (= Jervis) Markham (c.1568-1637) , son of Sir Robert Markham of Cotham, mastered several languages and was an accomplished Latinist, a horse breeeder, an author of lyrics and numerous treatises on husbandry.

So of the above-mentioned English sonneteers two were members of the aristocracy (Constable, Markham), seven entertained close ties to court circles through descent, activity or acquaintance with influential friends (Daniel, Barnes, Drayton, Fletcher, Barnfield, Spenser, Griffin). All of them must be accounted to belong to a circle having access to the literary manuscripts circulating, as then usual, at court.

Nobody would suppose Shake-speare had plagiarized Jervis Markham’s dedicatory poem from Devoreux, or Verities Tears (1597) or Bartholomew Griffin’s sonnets 14 and 39 from Fidessa (1596). Too obvious is their conscious imitative character– and above all: Francis Meres has told us that SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS were already in existence in 1598. So there is no need to reverse the course of influence.

The occasional poet Markham quotes Shake-speare’s sonnet 84

Who is it that says most, which can say more

Than this rich praise, that you alone are you,

varying it:

But you! ô you, you that alone are you,

Whom nothing but your selves your selves can match...

Bartholomew Griffin, author of Fidessa, 62 lover’s complaints in sonnet form, almost patently vies with the Master in sonnet 14, reminiscent of both Shake-speare’s sonnet 27 and the song “to Sylvia” from Two Gentlemen of Verona, III/1.

Shake-speare says:

For then my thoughts (from far where I abide)

Intend a zealous pilgrimage to thee,

And keep my drooping eyelids open wide,

Looking on darkness which the blind do see -

and:

My thoughts do harbour with my Silvia nightly,

And slaves they are to me, that send them flying.

O, could their master come and go as lightly,

Himself would lodge where (senseless) they are lying!

Griffin has:

When silent sleep had closèd up mine eyes,

My watchful mind did then begin to muse;

A thousand pleasing thoughts did then arise,

That sought, by slights, their master to abuse.

Similarly Griffin‘s sonnet 39. Whereas the tone of Shake-speare’s sonnet 130 is mildly ironical for the mistress:

My Mistress’ eyes are nothing like the Sun ...

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That Music hath a far more pleasing sound.

I grant I never saw a goddess go,

My Mistress when she walks treads on the ground –

Griffin, the competitor, strikes a harsher note:

My Lady’s hair is threads of beaten gold ...

Her smiles and favours sweet as honey be.

Her feet, fair Thetis praiseth evermore.

But ah, the worst and last is yet behind:

For of a griffon she doth bear the mind !

Back to the years 1595 and 1594, the references become more abundant in Richard Barnfield’s volumes Cynthia (1595) and The Affectionate Shepheard (1594).

Barely twenty years old, Barnfield published his maiden work The Affectionate Shepheard, causing some stir, for the youthful author of those homoerotic poems more or less openly confessed his sexual deviance, the which led to the reproval by his family and his disinheritance. Though he attempted to placate the interested reader in his preface to Cynthia (1595) in that he argued his Affectionate Shepheard would simply be an imitation of Virgil’s second eclogue to Alexis, the twenty sonnets of Cynthia, which openly continued style and subject of the previous work, gainsaid his denial.

Richard Barnfield (we should represent him somewhat in the fashion of Oscar Wilde with a green beret and mirror-smooth stockings) – but above all he was an unconditional admirer of Shake-speare whom he read and interpreted his way.

It was Barnfield who in 1598 for the first time praised Shake-speare in a poem:

And Shakespeare thou, whose honey-flowing Vein

(Pleasing the World) thy Praises doth obtain,

Whose Venus, and whose Lucrece (sweet, and chaste)

Thy Name in fame’s immortal Book have plac'd.

Live ever you, at least in Fame live ever:

Well may the Body die, but Fame dies never.

“The poet Barnfield,” the Shakepeare researcher and editor Sidney Lee (1859-1926) wrote, “who, in poems published in that and the previous year, borrowed with great freedom from Venus and Adonis (1593) and Lucrece (1594) levied loans on the SONNETS at the same time.” (Shakespeare’s Poems and Sonnets, ed. 1905.)

Today hardly one philologist deigns to refer to Lee’s observation.

To be precise: Barnfield took over poetical phrases and thoughts from Shake-speare’s two epyllions and seventeen SONNETS altogether. See TABLE I.

Evidently, the young author’s predilection went to those parts that made the deepest impression on him.

Shake-speare, 20:

But since she pricked thee out for women's pleasure,

Mine be thy love and thy love's use their treasure.

Barnfield, The Affectionate Shepheard:

I love thee for thy gifts, She for her pleasure;

I for thy Vertue, She for Beauty's treasure.

Shake-speare, 21

... my love is as fair

As any mother's child, though not so bright

As those gold candles fixed in heaven's air -

Barnfield, The Affectionate Shepheard:

Oh lend thine ivory forehead for Love's book,

Thine eyes for candles to behold the same -

Barnfield, Cynthia, Sonnet 4:

Two stars there are in one fair firmament,

Of some entitled Ganymede's sweet face -

Shake-speare, 53

Describe Adonis and the counterfeit

Is poorly imitated after you

Barnfield, Cynthia, Sonnet 17:

Cherry-lipt Adonis in his snowy shape

Might not compare with his pure ivory white,

On whose fair front a Poet's pen may write -

Shake-speare, 144

To win me soon to hell, my female evil

Tempteth my better angel from my side,

And would corrupt my saint to be a devil:

Wooing his purity with her foul pride.

Barnfield, The Affectionate Shepheard:

Thou dost entice the mind to doing evil,

Thou setst dissention twixt the man and wife;

A Saint in show, and yet indeed a devil:

Thou art the cause of every common strife –

In many cases Barnfield‘s borrowings look like citations. So he conjures the ghost of the deceased author in Greenes Funerall (1594) as follows:

Amend thy style who can: who can amend thy style?

The exclamation must be understood as allusion to Shake-speare's sonnet 78:

In others' works thou dost but mend the style –

That in this case Shake-speare cannot be the epigone should be clear to the staunchest defender of Shakespeare-the borrower-thesis.

Doubtlessly Richard Barnfield made use of SHAKE-SPEARE‘S SONNETS as early as 1594. Whence it must be inferred that Michael Drayton and Edmund Spenser, who published sonnets in 1594 and 1595 respectively, also belonged to the circle of “private friends”.

The learned poet Edmund Spenser, the creator of the Faery Queene, a poet with legitimate aspirations, also occasionally likes to borrow – with no intention of emulating – from an admired model. In his cycle Amoretti (written in 1594 and printed the year after) he alludes in particular to SHAKE-SPEARE in Sonnet XLIII.

Yet I my heart with silence secretly

will teach to speak, and my just cause to plead:

and eke mine eyes with meek humility,

love-learned letters to her eyes to read.

Here Shake-speare preceded him in sonnet 23:

O let my looks be then the eloquence,

And dumb presagers of my speaking breast,

Who plead for love, and look for recompense,

More than that tongue that more hath more expressed.

O learn to read what silent love hath writ:

To hear with eyes belongs to love’s fine wit.

Similarly, the prolific Michael Drayton, active and successful in many literary genres, profited from reading the Shakespearean epyllions and sonnets in the period between 1593 to 1599 to which he alludes and in the poetical mode “quotes” from several times. (With equal self-evidence Drayton uses Petrarch, Tasso, Baïf, Scève, de Ronsard, Gascoigne, Sidney, Spenser, Southwell and Barnes.)

Above all Drayton (portrayed with laurel wreath over the high forehead, the great brown eyes goodly directed to the observer) appropriates the immortality topos found in Shake-speare‘s sonnets in a largely uncritical manner. In 1599 he publishes his sonnet cycle Ideas Mirror. The forty-third sonnet (number XLIV in the 1619 edition) puts together- in the address to „Idea“- elements of Shake-speare’s sonnets 81, 68 and 32.

Whilst thus my pen strives to eternize thee

Age rules my lines with wrinkles in my face,

Where in the map of all my misery

Is modelled out the world of my disgrace.

Whilst, in despite of tyrannizing times,

Medea-like, I make thee young again,

Proudly thou scorn'st my world-outwearing rhymes

And murtherest virtue with thy coy disdain.

And though in youth my youth untimely perish,

To keep thee from oblivion and the grave

Ensuing ages yet my rhymes shall cherish,

When I entombed, my better part shall save;

And though this earthly body fade and

die,

My name shall mount upon eternity.

He who imitates in the year 1599 is likely already to have done so five years before. Drayton's 33rd sonnet „Whilst thus mine eyes do surfeit with delight“ from Ideas Mirror (1594), poor in thought and meter, emulates Shake-speare’s sonnets 46 and 47:

Whilst yet mine eyes do

surfeit with delight,

My woeful heart, imprisoned in my breast,

Wisheth to be transformèd to my sight,

That it, like those, by looking might be blest;

But whilst my eyes thus greedily do gaze,

Finding their objects over-soon depart,

These now the other's happiness do praise,

Wishing themselves that they had been my heart,

That eyes were heart, or that the heart were eyes,

As covetous the other's use to have;

But finding Nature their request denies,

This to each other mutually they crave:

That since the one cannot the other

be,

That eyes could think, or that my

heart could see.

On the basis of those parallels (completely listed in TABLE II) it needs a bold stretch to see Shake-speare as the imitator and Drayton as the honey-tongued genius.

Let us go back one step – to the crucial year 1593.

Crucial because apart from Alexander B. Grosart no Shakespeare researcher has been prepared to follow us into the obnubilated web of this year. (In the summer 1593 Shake-speare’s epic poem Venus and Adonis is published, with some of his plays being staged or about to. At the same time Will Shaksper makes his first appearance as payee of his company, subsequently to largely disappear from the view.)

Shakespeare‘s biographer Sidney Lee, otherwise a reliable guide, goes awol. What was true for Richard Barnfield in 1594 is no longer true for Barnabe Barnes in 1593. Lee considered the “poet Barnfield” an amiable thief — but he considers the lyrical upstart Barnes, author of only one extant collection of poems Parthenophe and Parthenophil (1593) Shake-speare’s master, and as the rival whom the master plagiarized!

“His [Barnes'] Sonnet LXXVI on Content,” writes Lee, “reaches a very high level of artistic beauty, and many single stanzas and lines ring with true harmony. But as a whole his work is crude, and lacks restraint. He frequently sinks to meaningless doggerel, and many of his grotesque conceits are offensive. To the historian of the Elizabethan sonnet his work is, however, of first-rate importance. No thorough investigator into the history of Shakespeare's sonnet can afford to overlook it. Constantly he strikes a note which Shakespeare clearly echoed in fuller tones... Shakespeare followed Barnes in his free use of law terms, by which the latter illustrates what he calls 'the tenure of love's service' (xx.); (cf. Barnes' Sonnet iv., ‘suborners,’ Sonnet viii., ‘mortgage,’ Sonnet xx., ‘rents’).” (An English Garner, Elizabethan Sonnets, ed. by Sidney Lee, vol. I., p. lxxv-vi. London 1904.)

Reverend A. B. Grosart (1827-1899) disagrees. And his vote is the weightier because nobody else knew Elizabethan literature better than he. Grosart has edited the complete works of Nicholas Breton, Giles Fletcher, Sir Philip Sidney, Edmund Spenser, Samuel Daniel, Robert Southwell, Sir John Davies, Fulke Greville, Barnabe Barnes, Richard Barnfield, John Davies of Hereford, Robert Greene, Gabriel Harvey, Thomas Nashe, Thomas Dekker and John Donne – not only has he read all of them, he has, as said, edited all of them, commented, described their strengths and weaknesses alike and carefully researched their lifes. For the bishop’s son Barnabe Barnes, 24 years old in 1593 and rather rash and confused, somewhat unstable and somehwat foolhardy, if not outright foolish, Grosart does not hide his sympathy and admiration, but it does not occur to him to see in Barnes Shake-speare's teacher:

“I think, too, that the thoughtful student of Parthenophil and Parthenophe will agree with me that there are analogies in these Sonnets and Madrigals that remind us, at any rate, that he might have seen some of those "sugred sonnets" which Meres, in 1598, spoke of as circulating among Shakespeare's friends. Nor is it to be overlooked, that while in the closing group of Sonnets at the end of Parthenophil and Parthenophe the Earl of Northumberland is called "mighty" and Essex "thrice valiant," the "right noble and vertuous lord, Henry earl of Southampton" — Shakespeare's Southampton, — is addressed as “sweet lord" — Shakespeare's own elect word in his sonnets.”

Carried away by the charm of feminity and his own excitement, Barnabe Barnes (his foe Thomas Nashe pokes fun at him, depicting him with “a pair of Babylonian breeches and a codpiece as big as Bologna sausage“ (Have with You to Saffron Walden, p. 62) reels off without interruption in 105 sonnets, 21 elegies, 3 songs, 5 sestines and 20 odes (enough to be scolded an idiot by William John Courthope in his History of English Poetry). A typical example is sonnet 49:

Cool cool in waves thy beams intolerable,

O sun, no son but most unkind stepfather,

By law nor nature sire, but rebel rather!

Fool fool, these labours are inextricable,

A burden whose weight is insupportable,

A Siren, which within thy breast doth bath her,

A Fiend which doth in grace’s garments graith her,

A fortress whose force is impregnable:

From my love's limbeck still still’d tears, O tears!

Quench quench mine heat, or with your sovereignty,

Like Niobe, convert mine heart to marble:

Or with fast-flowing pine my body dry,

And rid me from despair's chill’d fears, O fears!

Which on mine ebon harp's heart strings do warble.

Lines 2 and 9 of this baffling poem point to Shake-speares sonnets 7, 33 and 119. With the sun cooling his unsupportable beams in the waves (of his tears), Barnes means the beams from the eyes of his beloved; at the same time he means his own heart set aflame by the very same beams and metamorphed into a sun – and thereby he means the astrological sun controlling his fate. This glow burning from inside and outside is an inimical force, hence not like a loving son but a like a heartless stepfather. The pun on sun and son, which in Barnes‘ poem arises out of thin air withhout meaningful relation to the context, can be found in SONNETS 7 and 33. Equally obvious is the reference of line 9 - From my love's limbeck still still’d tears – in connection with the friendly-hostile siren (and the fear she provoke) to SONNET 119, which opens:

What potions have I drunk of Siren tears

Distilled from Limbecks foul as hell within –

Applying fears to hopes, and hopes to fears,

Still losing when I saw myself to win!

Shake-speare composes his stanzas in contrapuntal texture so as to evoke a compelling notion of pain, whereas the young Barnes piles up a rather amorphous heap of words reaped from Italian and French examples and from SHAKE-SPEARE’S SONNETS as well. With the same flippancy he usurps Shake-speares beauty’s Rose and Devouring time and purloins in his own clumsy self-satisfaction oozing sonnets (1-20) the master’s habit of using legal metaphors in love poetry. – The satirist Thomas Nashe (1567-1601) let not slip the occasion to poke fun at Barnes’s poetical efforts:

„What his scholarship is, I cannot judge, but if you have ever a chain for him to run away with, as he did with a nobleman's steward's chain at his lord's installing at Windsor, or if you would have any rimes to the tune of stink-a-piss, he is for you, in one place of his Parthenophil and Parthenophe wishing no other thing of heaven but that he might be transformed to the wine his mistress drinks, and so pass through her. - Therein he was very ill advised, for so the next time his mistress made water, he was in danger to be cast out of her favour.“ (Thomas Nashe, Have with you to Saffron-Walden, 1596).

Table III shows a comparison between Shake-speare vs. Barnes.

There is further an ethereal poem by Giles Fletcher the Elder, diplomat, Member of Parliament, and poet, who in 1593 published a collection of 52 sonnets under the title Licia. Fletcher, epigone par excellence , wrote love poems not out of a genuine feeling but essentially for didactic purposes, namely to make better known the poetry of the Continent in England through adaptations. He first recurred to the “best Latin poets“ but also to Pierre de Ronsard, Claude de Pontoux and Philippe Desportes, to Thomas Watson and Sir Philip Sidney. – His sonnet XXVII runs:

The Crystal streames wherein my love did swim,

Melted in tears as partners of my woe;

Her shine was such as did the fountain dim:

The pearl-like fountain whiter than the snow;

Then like perfume, resolvéd with a heat,

The fountain smoked, as if it thought to burn:

A wonder strange to see the cold so great,

And yet the fountain into smoke to turn.

I searched the cause, and found it to be this:

She touched the water, and it burned with love,

Now by her means it purchas’d hath that bliss,

Which all diseases quickly can remove.

Then if by you these streams thus blessed be:

(Sweet) grant me love, and be not worse to me.

Why the streams in which Fletcher’s imaginary love is swimming burst out into tears and why this woman, who does not exist, through her gloss darkens the pearl-like, snowwhite source is as little understandable as the curious circumstance that her splashing heats the water and confer it healing power. Mrs Licia, this much seems clear, is imitating little Cupid whose torch —according to Marianus Epigrammaticus and William Shake-speare – makes burn the cool well. But while there is no longer any question of Cupip in Fletcher’s version, he readily takes over Shakespeare’s transformation of the water into a spa: “a cool Well ... Growing a bath and healthful remedy / For men discased“ (154).

Compared with Fletcher’s sweetish plumpudding Shake-speare's often disregarded sonnets 153 and 154 look like hellenic temples.

It should by now be clear that SHAKE-SPEARE‘S SONNETS were known in London literary circles as early as 1593.

Whereby, en passant, the question whether Shake-speare imitated Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593) or vice versa is also settled. Marlowe wrote his epyllion Hero and Leander in the months before his death, hence, approximately between December 1592 and May 1593. At that time the SONNETS were already circulating in manuscript – and the epic poem Venus and Adonis was registered in the Stationers’ Register on on 18 April 1593. It is inconceivable that Hero and Leander (which we know was completed by George Chapman after Marlowe’s death on 30 May 1593) would have lain incompletely on Marlowe’s desk at the time of his murder. Shake-speare’s epic poem could hardly have been inspired by Marlowe’s still unfinished epic poem (which does not refrain the still dominating theory, for instance of Harold Bloom, from positing Marlowe’s influence on Shake-speare. – For the parallels between Marlowe and Shake-speare see TABLE IV.

At the risk of unduly wearying the reader, one remark ought to be added about the play Edward III, a rather mediocre drama which to write, either entirely or only partly, Shake-speare would have had no reason, the less so because, as Helen Vendler notes “Shakespeare rarely amuses himself the same way twice” (Helen Vendler, The Art of SHAKESPEARE’S SONNETS, Cambridge, MA, London, England, 1997, p. 31) - which he would have done in the said play, quoting the last line of his sonnet 94: “Lilies that fester smell far worse then weeds.” Together with „scarlet ornaments and bootless cries from sonnets 142 and 29 the borrowing of the line should be seen as the result of an accidental pick up – Edward III was composed in 1592 or 1593 and published anonymously in 1596 (happily, the play was not included in the Folio of 1623).

In the year 1592, to continue our retrospective tour, Samuel Daniel, an highly regarded author in his time, published his sonnet cycle Delia – „containing certain sonnets and the complaint of Rosamond.“ – Daniel, son of a musician, earned a living as private tutor in aristocratic households and author of court masks, and was abundantly lauded by his contemporaries. He has been portrayed with large round eyes, Roman nose, wavy hair, open wing collar, and pointed hat. - Michael Drayton in 1593 extolled Daniel as the arcadian shepherd who has wisely led his flock (Good Melibeus, that so wisely hast / Guided the Flocks delivered thee to keep), Richard Barnfield praised him for his “sweet-chast Verse” (1598), Henry Chettle addressed him as “Thou sweetest song-man of all English swains” (1603).

About half of his sonnets from Delia were surreptitiously printed as early as in 1591 — which throws us back by a full year.

The general consense (almost sole laudable exception was Hermann Isaac, teacher at the cadet school in Berlin-Großlichterfelde) is that William Shakespeare was indebted to Samuel Daniel, not the other way round. Shake-speare, we are told, would have worked his way through Samuel Daniel, to have quoted from him in 16 sonnets and two epic poems - and borrowed from him.

Yet the theory of Daniel being Shake-speare’s precursor cannot stand up to closer scrutiny.

Enter a lean gentleman with rimmed glasses, a dyed-in-the wool critique and sceptic by profession. And this gentleman, points with raised finger, politely but reproachfully, to Daniel’s sonnet XXX (1591) which clearly shows a similarity with Shake-speare’s SONNET 63: less so for vocabulary than basic theme. Looking toward to the future, both poets envision how the beauty of their (or his) beloved will have perished but will live forth in their respective songs.

|

Daniel XXX

|

Shake-speare, 63 |

|---|---|

|

I once may see when years shall wreck my wrong, And golden hairs shall change to silver wire, And those bright rays that kindle all this fire, Shall fail in force, their working not so strong, Then beauty, now the burden of my song, Whose glorious blaze the world doth so admire, Must yield up all to tyrant Time's desire; Then fade those flow’rs that deck’d her pride so long. When if she grieve to gaze her in her glass, Which then presents her whiter-withered hue, Go you, my verse, go tell her what she was, For what she was, she best shall find in you. Your fiery heat lets not her glory pass, But phoenix-like shall make her live anew. |

Against my love shall be as I am now With time’s injurious hand crushed and o’erworn, When hours have drained his blood and filled his brow With lines and wrinkles, when his youthful morn Hath travelled on to Age’s steepy night, And all those beauties whereof now he’s King Are vanishing, or vanished out of sight, Stealing away the treasure of his Spring: For such a time do I now fortify Against confounding Age’s cruel knife, That he shall never cut from memory My sweet love’s beauty, though my lover’s life. His beauty shall in these black lines be seen, And they shall live, and he in them still green. |

However, Samuel Daniel himself here imitates Torquato Tasso’s “Vedrò da gli anni in mia vendetta ancora” Why should Shake-speare, who was not less well-read than Daniel, have contented himself with Daniel’s anglification ?

Also line 7

Must yield up all to tyrant Time's desire

strikingly reminds the tyrant time in Shakespeare’s SONNET 16:

But wherefore do not you a mightier way

Make war upon this bloody tyrant time?

Not without reason have Elizabethan contemporaries mocked Daniel’s plagiarizing art:

Sweet honey-dropping Daniel doth wage

War with the proudest big Italian,

That melts his heart in sugar’d sonneting;

Only let him more sparingly make use

Of others’ wit, and use his own the more,

That well may scorn base imitation.

The Return from Parnassus II.

I.ii. (1601)

As similarly unscrupled imitator Daniel adapted poems of Francesco Petrarch, Torquato Tasso, Luigi Tansillo, Battista Guarini, Joachim du Bellay and Philippe Desportes and incorporated them as if they were his own poems. He several times revised his sonnets for the four issues of Delia, thereby dropping some things and adding others — frequently using poetical turns he had come across in his favourite authors. - TABLE V.1 informs about some of the authors from whom Daniel borrowed.

Theoretically Shake-speare could have been a second-hand borrower. However, Daniel betrays himself, for the author of Delia prolongued his habit of imitating Shake-speare in 1594 and 1601. And in those years, Shake-speare’s SONNETS, who will doubt it?, were already circulating “among his private friends”.

Shake-speare, 38:

If my slight Muse do please these curious days,

The pain be mine, but thine shall be the praise.

Drayton, Dedication poem to Lady Mary Pembroke (1594)

Whereof, the travail I may challenge mine;

But yet the glory, Madam! must be thine!

Shake-speare, 142:

those lips of thine ...

Robbed others' beds' revenues of their rents.

Drayton, Rosamond (ed. 1594)

And in uncleanness ever have been fed,

By the revenue of a wanton bed.

Shake-speare, 19:

Devouring time ... And do whate'er thou wilt…

But I forbid thee one most heinous crime,

O carve not with thy hours my love's fair brow -

Shake-speare, 126:

O thou my lovely Boy who in thy power

Dost hold time’s fickle glass, his sickle, hour -

Drayton, Sonnet XXIII (1601)

Time, cruel Time, come and subdue that brow

Which conquers all but thee, and thee too stays,

As if she were exempt from scythe or bow,

From love or years unsubject to decays...

Yet spare her, Time, let her exempted be,

She may become more kind to thee or me.

Daniel’s masquerades prompted Ben Jonson to an excoriating judgement:

„Samuel Daniel was a good honest man, had no children; but no poet ... Daniel wrott civill warres; and yett hath not one batle in all his book (Conversations with Drummond of Hawthornden, 1619, pp. 3, 20)

However, it will be objected, that in his epyllion The Rape of Lucrece Master Shakespeare (without hyphen) would have followed Daniel’s romance The Complaint of Rosamond complementing the sonnet cycle Delia, demonstrably in existence since 1592. The Rape of Lucrece, on the contrary, was not published until 1594, one year after Shakespeare in his preface to Venus and Adonis (1593) announced the forthcoming publication of that work “I vow to take advantage of all idle hours, till I have honoured you with some graver labour.” – But to begin with, the publication of a work cannot be equated to the date of composition. However, to begin with considerable time can elapse before the publication. (Büchner‘s Woyzeck was written in 1836 but no published until 43 years later). Secondly, the shallow, pathetic lamentations of the tearful Rosamond can hardly be compared with the refined discourse of the heroical Lucrece. (And also in this case Daniel reiterates his imitation procedure in different editions till 1601). So that we feel authorized to conclude that Shake-speare (with hyphen) had already finished his epic poem The Rape of Lucrece (including the courteous-courtly dedication) three years before it was printed. [iv]

The reader is invited to take in charge the reading of TABLE V.2, in which the relationship Shake-speare - Daniel is more amply dealt with.

Last but not least we must now turn to Henry Constable, one of the first English sonneteers whose sonnet cycle Diana was printed in 1592 (In the wake of Sidney’s Astrophel and Stella in 1591). However, the eloquent courtier had already left England, for ironically our author had lost his Protestant faith over writing a tract in defense of it. In the Summer of 1591 Constable had left country, family, and possessions. His sonnets are dedicated to the beautiful ladies of the courts. The greatest part of it were written between 1589 and 1590. Though he assiduously accumulated passionate exclamations and has come to be considered the pioneer of the English sonnet poetry, Henry Constable was by no means an original genius. He too was after all an honest man and poor poet. Three examples of his lyrical passion might suffice to demonstrate it.

|

William Shake-speare, 106

|

Henry Constable, Todd’s MS., III.4

|

|---|---|

|

When in the Chronicle of wasted time, I see descriptions of the fairest wights, And beauty making beautiful old rhyme, In praise of Ladies dead, and lovely Knights, Then in the blazon of sweet beauty’s best, Of hand, of foot, of lip, of eye, of brow, I see their antique Pen would have expressed Even such a beauty as you master now. So all their praises are but prophecies Of this our time, all you prefiguring, And for they looked but with divining eyes, They had not skill enough your worth to sing: For we which now behold these present days, Have eyes to wonder, but lack tongues to praise. |

Miracle of the world! I never will deny, That former poets praise the beauty of their days; But all those beauties were but figures of thy praise, And all those poets did of thee but prophesy. Thy coming to the world hath taught us to descry What Petrarch's Laura meant, for truth the lip bewrays. Lo, why th' Italians, yet which never saw thy rays, To find out Petrarch's sense such forged glosses try! The beauties which he in a veil enclosed behold, But revelations were within his surest heart, By which in parables thy coming he foretold; His songs were hymns of thee, which only now before Thy image should be sung; for thou that goddess art Which only we without idolatry adore. |

Shake-speare has by no means plagiarized older authors - be it Ovid, Horace, Petrarch, Tasso, Du Bellay, Jodelle, Chaucer or Sidney. As a “learned writer” he has consciously digged into his precursors and picked up some passages, paraphrased and transcended them (to a very moderate extent).

As J. B. Leishman put it, „Shakespeare transfigured and Shakespeareanised his reading to a far greater extent than any other Renaissance poet.“(J. B. Leishman, Themes and Variations in Shakespeare’s sonnets, London, 1961, p. 62.)

Who then could believe that he had integrally borrowed SONNET 106, including matter and manner, from the occasional poet Henry Constable ? From a poet who as a general rule imitated Petrarch, Serafino, Costanzo, Scève, Mellin de Saint-Gelais and Desportes, and whose poem “Miracle of the world!” was only printed in the 19th century. Shake-speare’s line “Let not my love be called Idolatry” in sonnet 105, too, would then be derived from Constable’s distorted rendering: “for thou that goddess art / Which only we without idolatry adore”?

And further: how then would Master Daniel , who wrote in the same period as Constable, have come to his own line in XLVI („Let others sing of Knights and Paladines“), which for idea and formulation is also suspiciously reminiscent of SONNET 106?

Now to the second comparison:

|

145

|

Marsh Ms. |

|---|---|

|

Those lips that Love’s own hand did make, Breathed forth the sound that said I hate, To me that languished for her sake: But when she saw my woeful state, Straight in her heart did mercy come, Chiding that tongue that ever sweet Was used in giving gentle doom: And taught it thus anew to greet: I hate she altered with an end, That followed it as gentle day Doth follow night who like a fiend From heaven to hell is flown away. I hate, from hate away she threw, And saved my life saying not you. |

My hope lay gasping on his dying bed, Slain with a word, the dart of thy disdain: Another word breathed life in it again, And staunched the blood my wounded hope had shed. Sweet tongue then sith thou canst revive the dead, Thou easily mayst assuage a sick man's pain; What glory then shall such thy power gain, Which sickness, health, which life and death hast bred? One word gave life, one word can health restore; If no? I live: but live as better no; More thou speakest not, and if I call for more, More is thy wrath, and thy wrath breeds my woe. My tongue and thine thus both conspire my smart, Mine while I speak, thine while thou silent art. |

(The parallel with “More thou speakest not, and if I call for more,/ More is thy wrath” and SONNET 23: „More than that tongue that more hath more expressed“.)

To the proponents of Constable‘s important role as a precursor it must, morerover, be pointed out that the sonnet about the gasping hope was not discovered and subsequently printed until 1898 by Edward Dowden in an old manuscript he found in Dublin. To believe this the incredible assumption must be made that the actor Will Shaksper had been sniffing in the library of his friend Henry Wriothesley to dig out a copy of this curiosity.

Third non-starter- Henry Constable‘s often quoted poem “My Lady’s presence makes the Roses red” (Sonnetto decisette from the Diana cycle of 1592), often said to be the source for SONNET 99.

|

Sonnet 99

|

Sonnetto decisette (ed. 1592)

|

|---|---|

|

The forward violet thus did I chide: “Sweet thief, whence didst thou steal thy sweet that smells, If not from my love’s breath? The purple pride Which on thy soft check for complexion dwells, In my love’s veins thou hast too grossly dyed.” The Lily I condemned for thy hand, And buds of marjoram had stol'n thy hair, The Roses fearfully on thorns did stand, One blushing shame, another white despair: A third nor red, nor white, had stol'n of both, And to his robbery had annexed thy breath, But for his theft in pride of all his growth A vengeful canker eat him up to death. More flowers I noted, yet I none could see, But sweet, or colour it had stol'n from thee. |

My Lady’s presence makes the Roses red, because to see her lips, they blush for shame: the Lilly’s leaves (for envie) pale became, and her white hands in them this envie bred. The Marigold the leaves abroad doth spread, because the suns: and her power is the same: the Violet of purple colour came, dy'd in the blood, she made my heart to shed. In brief, all flowers from her their vertue take; from her sweet breath their sweet smells do proceed; the living heat which her eye-beams doth make, warmeth the ground, and quickeneth the seed. The rain wherewith she watereth the flowers, falls from mine eyes, which she dissolves in showers. |

After the previous comparisons, little remains to be added about Henry Constable’s paper roses, lilies and violets.

In short: Henry Constable has set us with courteous clarity on a journey back into the year 1590. For after his emigration from England for religious motives in the Summer of 1591 he wrote but religious poetry.

For further coincidences see Table VII.

If we put the fateful year 1588 for sonnet 107 as terminus ante quem and understand the three winters, three springs and three summers of sonnet 104 literally, we obtain the years 1589/90 till 1591/92 as the probable period of composition of the SONNETS.

Insights from tabular synopsis

Tables I to VII contain the main text parallels between SHAKE-SPEARE and contemporary sonneteers.

However, the comparisons will reveal their information only to him that can interpret them correctly. Insofar the philological tables resemble the old astrological tables preceding a consistent cosmology.

In Table VIII are listed the imitations of SONNETS 1-154 in the period 1590-1601. This provides a systematic survey of the imitative occurences leading to logical conclusions.

Out of a total of 76 parallels to text passages from 53 (!) SONNETS some appear to be particularly revealing.

|

Sonnet

|

Imitator |

Work |

Year |

No. /line |

|

19 |

Samuel Daniel |

Delia |

1592 |

XLVI |

|

19 |

Barnabe Barnes |

Parthenophil and Parthenope |

1593 |

Dedic. / Eleg. 15 |

|

19 |

Samuel Daniel |

Delia |

1601 |

XXIII |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

46 |

Henry Constable |

Diana |

1590-91, ed. 1592 |

Sonn. dodeci |

|

46 |

Barnabe Barnes |

Parthenophil and Parthenope |

1593 |

S 20 |

|

46 |

Michael Drayton |

Ideas Mirror |

1594 |

XXXIII |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

68 |

Richard Barnfield |

Cynthia |

1595 |

S 12 |

|

68 |

Bartholomew Griffin |

Fidessa |

1596 |

11 |

|

68 |

Michael Drayton |

Ideas Mirror |

1599 |

43 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

106 |

Henry Constable |

Diana (Manuscript) |

1590-91 |

Todd III.4 |

|

106 |

Samuel Daniel |

Delia |

1592 |

XLVI |

|

106 |

Barnabe Barnes |

Parthenophil and Parthenope |

1593 |

Canz. 1 |

|

106 |

Richard Barnfield |

Cynthia |

1595 |

S 12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

142 |

Samuel Daniel |

Delia |

1592.2 |

XXVII |

|

142 |

Barnabe Barnes |

Parthenophil and Parthenope |

1593 |

S 20 |

|

142 |

Anonymous |

The Reign of King Edward III |

1592-93, ed. 1596 |

II/1 |

|

142 |

Samuel Daniel |

The Complaint of Rosamond |

1594 |

755-756 |

SONNET 19 contains parallels to Samuel Daniel’s sonnets from the years 1592 and 1601, which allows us an assessment of Daniel’s imitation skills.

Michael Drayton's reference to SONNET 68 in 1599 shows him to be the imitator.

The three or fourfold references to SONNETS 19, 46, 68, 106 and 142 unmistakingly reveal the dependence of the minor poets, who within a period of ten years are undertaking variations of an idea or image and in doing this quote or plagiarize significant coinages. Logically it makes no sense to suppose William Shake-speare could have patched together his sonnets 106 and 142 from books (and one manuscript) published in the years between 1592 and 1596. Even an author like SHAKE-SPEARE would not be able of that – even in his case it would have produced nothing more than a jumble of words.

But set apart the “art of tabulating” – it is almost ununderstandable why nobody has ever systematically investigated what was the cause that so many English minor poets between 1591 and 1595 in their slightly psychedelic Delias, Licias, Ideas and Dianas sudddenly started aspiring at immortal literary fame and unanimously indulging in erotic lamenting ?

Translated by Robert Detobel.

[i] John Lea (1589) speaks of “a horned Moone of huge and mighty ships”. "Now to make this Holy League an able body, to bear down upon the adversaries of Antichrist both by land and sea, her head was beautified with a horned Moon of huge and mighty ships, ready to join with the bloody Guise and also to unite them to the Prince of Parma… But all is vain: for the breath of the Lord’s mouth hath dimmed the brightness of her [the League’s] Moon, and scattered those proud ships." (The birth, purpose, and mortall wound of the Romish holie League: Describing in a mappe the envie of Sathans shavelings, and the follie of their wisedome, through the Almighties providence. By I[ohn] Lea [Leigh]. London 1589.

The unknown I. Lea or Leigh wrote a second treatise that praised the Earl of Oxford as a warrior during the war against the Armada: An answer to the untruthes, published and printed in Spaine, in glorie of their supposed victorie atchieved against our English Navie (1589)

De Vere, whose fame and loyalty hath pearst [pierced]

The Tuscan clime, and through the Belgike lands

By wingèd Fame for valour is rehearst,

Like warlike Mars upon the hatches stands.

His tusked Boar 'gan foam for inward ire,

While Pallas filled his breast with warlike fire.

[ii] and in 1590 the Italian soldier and scholar in English service Petruccio Ubaldini (1524-1600) wrote. "The next morning, being the twenty-first of July [1588], all the ships, which were now come out of the Haven, had gotten the wind of the Spaniards; and approaching somewhat nearer, found that their fleet was placed in battle array after the manner of a moon crescent, being ready with her horns, and her inward circumference, to receive either all, or so many of the English navy, as should give her the assault, her horns being extended in wideness about the distance of eight miles, if the information given have not deceived my pen." (A Discourse, concerning the Spanish Fleet invading England, in the Year 1588… Written in Italian, by Petruccio Ubaldino … and translated for A. Ryther. [London] 1590.)

[iii] The prophecy was published for the first time in 1557 by Cyprian of Leowitz.

Tausent fünffhundert

achtzig acht /

Das ist das Jar das ich betracht.

Geht in dem die Welt nicht under /

So gschicht doch sunst groß mercklich wunder.

Cyprian of Leowitz, Ephemeridum novum, 1557, fol. ee10v.

[iv] Shake-speare had already finished his epic poem The Rape of Lucrece three years before it was printed.

From another quarter we obtain a hint that the composition of The Rape of Lucrece had already been in place in 1591. Robert Southwell (1561-1595), son of the Catholic countrygentleman Richard Southwell, entered the Jesuit order at a young age, was ordained priest in Rom in 1584 and clandestinely returned to England on a mission to reconvert Protestant England in 1586, then considered an act of high treason. He found shelter within the Catholic gentry, but was arrested in June 1592, tortured and hanged in 1595. Southwell was an engaging preacher and talented poet; he considered poetry as integral part of his religious mission, probably to gain a foothold among the poetry-loving gentry. It was his aim to redirect profane love poetry to sacred subjects, to weave poems in the secular poets' “own loom”, as he wrote himself. Two such “looms” can definitely be identified. He adapted Sir Edward Dyer’s “He that his mirth hath lost” (into “A Sinner’s complaint”) and Edward de Vere’s “My mind to me a kingdom is” (into “Content and Rich”). Southwell’s Mary Magdalen's Funeral Tears inspired Thomas Nashe’s Christ’s Tears over Jerusalem . Other works were St.Peter's Complaint and The Triumphs over Death. Mary Magdalen’s Funeral Tears and St. Peter’s Complaint were first printed anonymously in 1591. Besides, Southwell’s poems contains several allusions and references to Shakespeare’s “heathen poetry” Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece.

In The Cambridge History of English and American Literature (Vol. IV, 1909) Harold H. Child writes:

“There can be no doubt that Southwell had read Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis, which was published in 1593 and at once became the most popular poem of the day. He seems, indeed, to have regarded it as the capital instance of the poetry he wished to supplant. His Saint Peters Complaint, published in 1595, soon after his death, is written in the metre of Shakespeare’s poem, and the preliminary address from the author to the reader contains a line, ‘Stil finest wits are stilling Venus’ rose,’“

Child had perhaps been less outspoken, if he had realised that Southwell no longer wrote poems, once arrested. – The persecuted Jesuit was thrown into a dirty dungeon, for months subjected to torture and distressing interrogation. Had he written literary works during his twoandhalf’s years imprisonment, his writings would have been protocoled and silently disposed of.

Historical fact is that Robert Southwell SJ terminated his spiritual poetry with his arrest in June 1592. And as he refers to Shake-speare‘s two epic poems, those poems must have been available in manuscript as early as end 1591.

But even more! Southwell not only weaved his own poets on Shake-speare’s loom, he even dedicated those poets to him.

The preamble to Saint Peters Complaint (see below) is headed: To my Worthy Good Cousin Master W.S.

„Poets, by abusing their talent, and making the follies and faynings of love the customarie subiect of their base endeavours, have so discredited this facultie, that a poet, a lover, and a liar, are by many reckoned but three words of one signification. But the vanitie of men cannot counterpoyse the authoritie of God, Who delivering many parts of Scripture in verse, and, by His Apostle willing us to exercise our devotion in hymnes and spiritual sonnets, warranteth the art to be good, and the use allowable. And therefore not onely among the heathen, whose gods were chiefely canonized by their poets, and their paynim divinitie oracled, in verse, but even in the Olde and Newe Testament, it hath beene used by men of greatest pietie, in matters of most devotion. Christ Himselfe, by making a hymne the conclusion of His Last Supper, and the prologue to the first pageant of His Passion, gave His Spouse a methode to imitate, as in the office of the Church it appeareth ; and to all men a patterne, to know the true use of this measured and footed stile.

But the devill, as he affecteth deitie and seeketh to have all the complements of divine honour applyed to his service, so hath he among the rest possessed also most Poets with his idle fansies. For in lieu of solemne and devout matter, to which in duety they owe their abilities, they now busie themselves in expressing such passions as onely serve for testimonies to what unworthy affections they have wedded their wills. And, because the best course to let them see the errour of their Works is to weave a new webbe in their owne loome, I have heere laide a few course threds together, to invite some skilfuller wits to goe forward in the same, or to begin some finer peece; wherein it may be scene how well verse and vertue sute together.

Blame me not (good Cosin) though I send

you a blameworthy present; in which the most that can commend it is the good

wit of the Writer; neither arte nor invention giving it any credite. If in me

this be a fault, you cannot be faultlesse that did importune me to commit it,

and therefore you must have part of the penance when it shall please sharp

censures to impose it.

In the meane time, with many good wishes, I send you these fewe ditties; adde

you the tunes, and let the Meane, I pray you, be still a part in all your

musicke.“

And this dedication is followed by the poetic lines “The Author to the Reader” :

So ripe is vice, so green is virtue's bud,

The world doth wax in ill, but wane in good.

This makes my mourning muse dissolve in tears,

This themes [teems] my heavy pen to plain in prose;

Christ's thorn is sharp, no head his garland wears ;

Still finest wits are 'stilling Venus' rose :

In paynim toys the sweetest veins are spent ;

To Christian works few have their talents lent.

Licence my single pen to seek a phere ;

You heavenly sparks of wit shew native light.

Cloud not with misty loves your orient clear,

Sweet flights you shoot, learn once to level right.

Favour my wish, well-wishing works no ill ;

I move the suit, the grant rests in your will.

In the first edition of Saint Peters Complaint (1595) the dedication reads The Author to his loving Cousin. The dedication „To my Worthy Good Cousin Master W. S.“ was added in the St. Omer edition of 1616 (after matching the handwriting). In the St. Omer R.S. subscribes as Your loving Cousin. – It could have done damage to Master W. S. , had he been publicly connected with a prominent Catholic in 1595, the very same year Southwell was executed for high treason.

.